Australia has the means to ensure that children and young people can thrive. Yet, for decades, evidence has shown stagnation or decline in key health and wellbeing outcomes and equity for many children and young people.1 Investment in prevention remains limited,2 policy settings in sectors that support health and wellbeing (such as public education) have been consistently underfunded,3 and harmful environments (such as marketing of unhealthy products) have been allowed to flourish.1 The Future Healthy Countdown 2030 (the Countdown) is designed as a high level, evidence‐based tool to advocate for change by shining a light on the outcomes and environments, such as education settings, that matter for children and young people.

Progress reporting for the Countdown provides an objective and pragmatic approach to tracking how Australia is delivering for children and young people across seven interconnected domains that are essential to health and wellbeing (eg, learning and employment pathways, explored in the current supplement). This article is the first progress report for the Countdown. In it, we assess Australia’s record against 22 outcome measures for the domains, showing how Australia’s children and young people are faring and how environments are delivering for their societal needs. We also report on eight proposed policy actions (one per domain and one overarching legislative action) that will improve Australia’s performance against these measures, including community sentiment for each policy action. Implementing these policy actions and improving the results of outcome measures by 2030 will benefit children and young people now and build a fairer future for generations to come.

Approach

The Countdown progress report

The seven domains essential for children and young people to thrive (Box 1) were adapted from The Nest framework developed by the Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth;5 details of the adaptation process have previously been described.4 In our 2024 consensus statement, we described how we operationalised the annual Countdown progress reporting through a robust consensus‐building process together with young people, researchers and policy experts — defining its rationale, outcome measures and policy actions.1 This process resulted in 2–4 measures and one policy action per domain, along with an overarching legislative policy action to anchor long term systemic change. For some domains, we chose measures that may not perfectly capture progress due to gaps in the availability, timeliness and generalisability of more relevant measures. In addition, we acknowledge that data alone are insufficient to understand the diverse experiences and voices of children and young people across Australia. This is particularly true for the domains “Positive sense of identity and culture” and “Valued, loved, safe”, where we rely on deficit measures that are less than ideal. The complexities of measurement in these domains have been described in previous Countdown publications.6,7

Tracking outcome measures

Our 22 measures draw on existing population‐level secondary data and are designed to track progress in each domain. Within some measures, we disaggregate by age bands, population subgroups or sub‐measures. Our data sources vary; we have used national surveys, administrative data and census data collected across different periods. This heterogeneity means that annual progress reporting is not always possible and that caution is required when comparing progress across measures and domains.

Progress was assessed by comparing the most recent data available to baseline data from 2023 (the year the Countdown was launched) or the most recent data as of 2023. When two datapoints are available, progress is assessed as positive (green arrow), negative (red arrow) or negligible (yellow line). Given the heterogeneity across measures, we interpret progress subjectively by considering the level of change that would shift the distribution on each measure at the population level8 and looking at precision estimate overlaps at both timepoints where available. We also flag two distinct types of data gaps: no new data (black circle), reflecting measures with regular collection cycles expected to capture future progress, and lack of regular and timely data (red circle with cross), reflecting systemic insufficiencies in measurement infrastructure.

National targets are available for eight measures (including four from Closing the Gap), with only seven having clearly defined target values, which underscores an accountability gap. Where new data became available since 2023, we assessed the magnitude of the change between the two timepoints as either on track or off track to achieve the target. Full details on each measure, including data sources, technical notes and interpretation, are provided in the Supporting Information.

Tracking policy actions

Our eight policy actions were selected to reflect realistic and impactful systems‐level national reforms, building on existing momentum. For each, we briefly outline recent policy activity, such as policy and funding changes, and report on community sentiment to identify where momentum for change is growing — whether driven by public support, political leadership, or both.

To assess community sentiment, we developed a suite of plain‐language questions designed to gauge public support for or opposition to each policy action (Supporting Information, supplementary table A). These were included in the 2025 Australian Unity Wellbeing Index survey, a nationally representative survey of nearly 10 000 Australian adults (mean age, 49.6 years [SD, 18.1 years]; 55.2% female) (Supporting Information, supplementary table B), conducted between 2 June 2025 and 26 June 2025 with ethics approval from Deakin University Human Research Ethics Committee (HEAG‐H 45_2016). The survey was administered by the Social Research Centre using: Life in Australia, Australia’s only probability‐based online panel (7822 respondents [79.0%]), and LiveTribe, a supplementary non‐probability‐based panel (2083 respondents [21.0%]) used to boost sampling from under‐represented demographic groups (eg, young male participants). Results from these panels were combined and weighted (Supporting Information, supplementary table C) and a sensitivity analysis showed that respondents from the smaller non‐probability‐based panel were more likely to express neutral rather than supportive views on most questions (Supporting Information, supplementary table D), likely due to differences in demographic factors such as age between the two panels. Notably, the overall sample including both panels aligned more closely with the 2021 Australian population characteristics than the sample that only included the larger probability‐based panel (Supporting Information, supplementary table B). Community sentiment on each item by age group is presented in the Supporting Information (supplementary figures 1–8).

Participants rated their level of support for each proposed government action on a 7‐point Likert scale, from strongly oppose to strongly support, with a neutral midpoint. In this article, we define policy support as responses of somewhat support, support or strongly support and define opposition as responses of somewhat oppose, oppose or strongly oppose. Survey weights were applied to align the sample with national population benchmarks, and all findings are reported as weighted estimates to maximise generalisability.

A limitation of the policy sentiment questions is phrasing bias towards implementation. This reflects the practical need for concise and accessible wording in a short survey. It is unlikely to affect comparisons across domains or age groups, or the substantive interpretation of findings. Full question and scale wording, methodological details, and estimates and confidence intervals by age group are provided in the Supporting Information.

Reporting on progress

We report progress in two sections. First, we present a high level summary of trends across the 22 measures, including progress and whether targets are on track (where available), plus a summary of community sentiment toward the eight policy actions. Second, we provide a more detailed account of outcome and policy progress within each domain.

Summary of progress

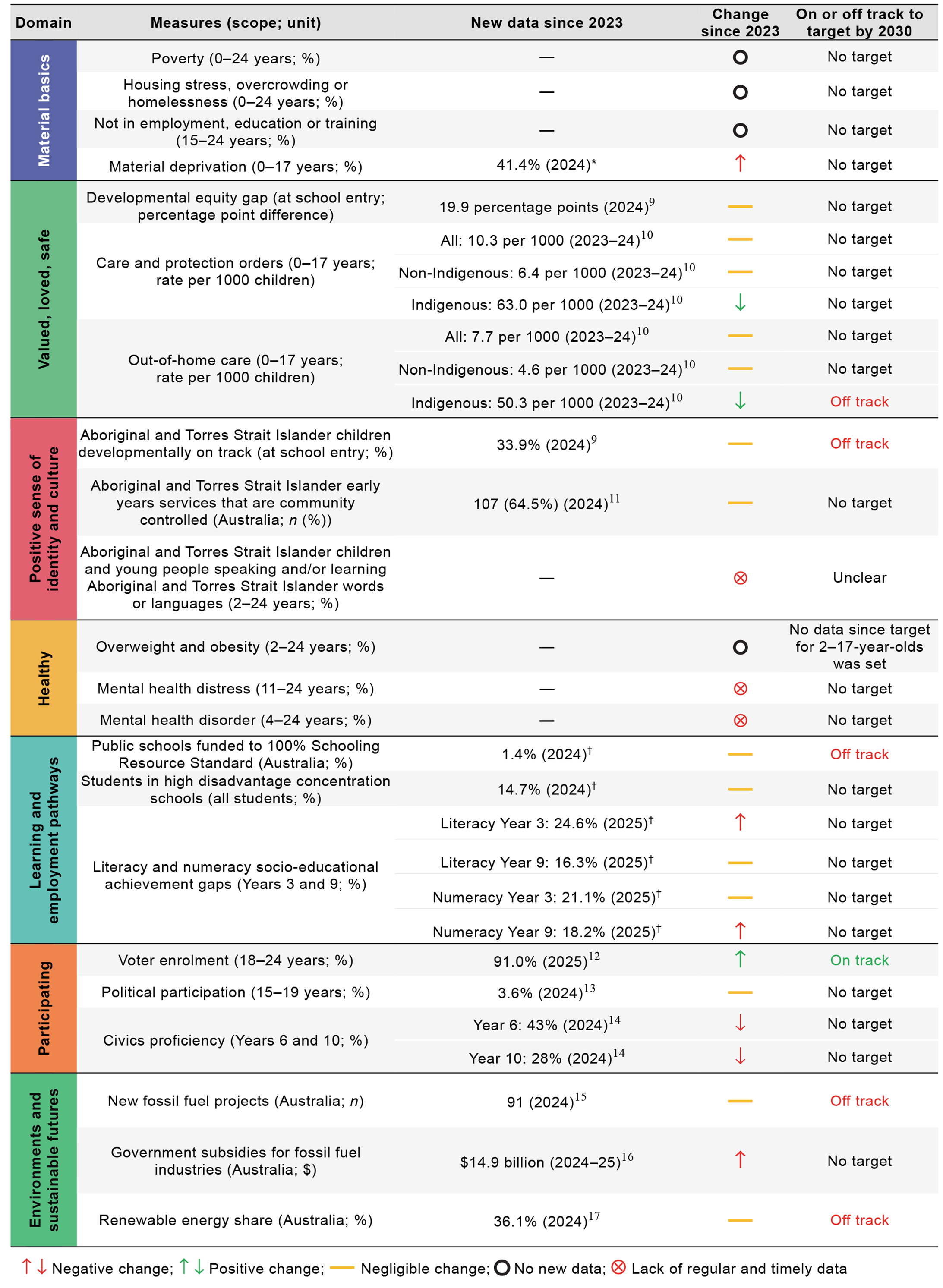

Outcome measures

Progress across the 22 outcome measures reveals that of the 15 measures (68%) from six domains with new data available, only one — voter enrolment rates — shows progress in the right direction (Box 2). Three measures show movement in the wrong direction — material deprivation, civics proficiency, and government subsidies for fossil fuel industries. The remaining 11 show mixed progress (three measures) or negligible progress (eight measures). The “Healthy” domain is particularly affected by a lack of regular, timely data, with the most recent population‐level data on children’s mental health collected more than a decade ago. Of the eight measures with national targets, seven were clearly defined, but only one was on track for meaningful improvement by 2030 — voter enrolment rates.

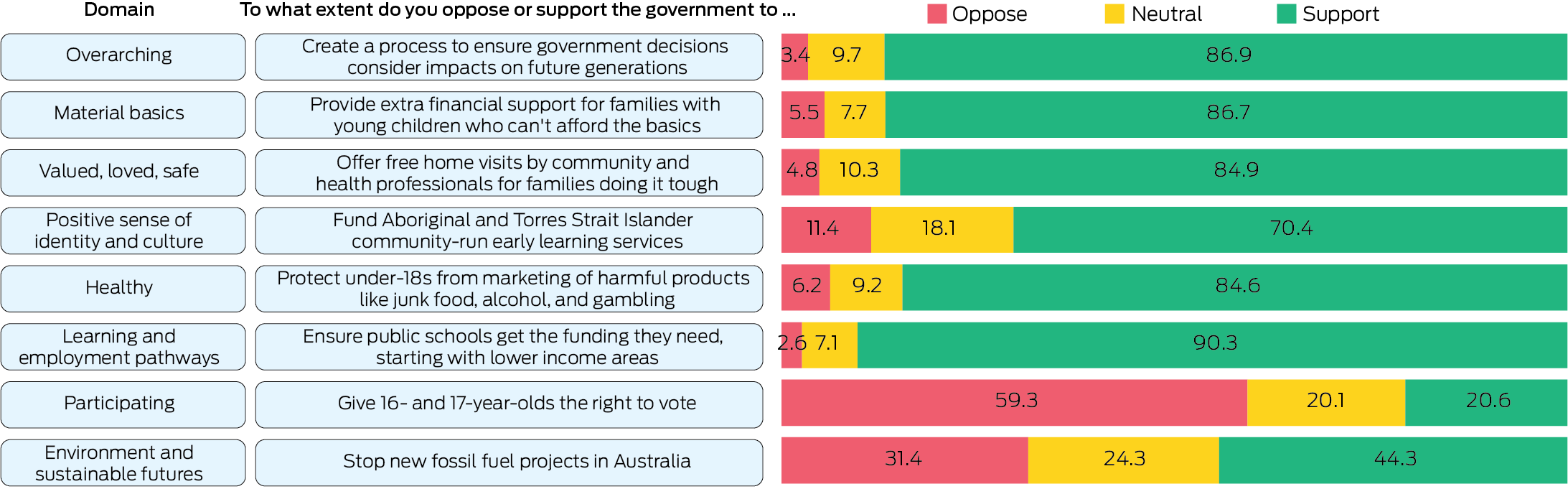

Community sentiment towards policy actions

There is strong public appetite for government action on most of the Countdown’s recommended polices. Six of the eight received high levels of support (supported by more than 70% of respondents), indicating broad public backing (Box 3). Support was mixed for stopping new fossil fuel projects and notably lower for extending voting rights to 16‐ and 17‐year‐olds. The most widely supported policy action was ensuring public schools are properly funded, starting with those in lower income areas.

Progress across domains and overarching policy action for future generations

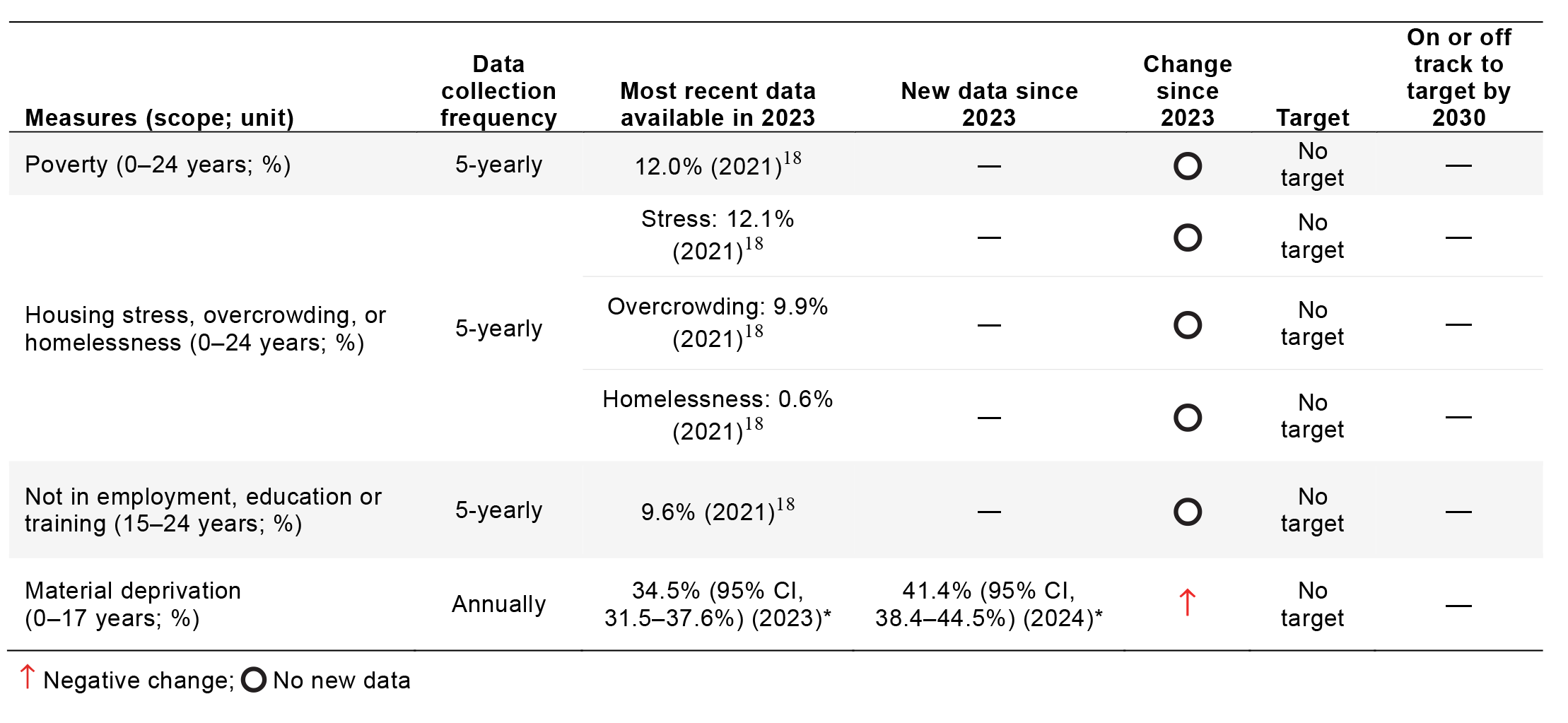

Material basics

Access to material basics, including safe housing, nutritious food and essential goods, is fundamental to children and young people’s health, development and wellbeing.18 From 2023 to 2024, the proportion of caregivers of children aged 0–17 years reporting material deprivation rose by 6.9 percentage points, indicating a growing inability of families to meet essential needs (Box 4). No new data were available for poverty, housing insecurity and the rate of young people not in employment, education or training. The national census, conducted every 5 years, is the only consistent mechanism by which these outcomes can be measured. Five‐yearly data intervals make it difficult to track hardship in real time, and this is compounded by the lack of a national definition of poverty and reliance on defaulting to limited poverty line measures,19 which fail to capture the multidimensional nature of poverty and disadvantage.

The 2025–26 federal budget introduced some cost‐of‐living relief measures, including energy bill rebates and expanded bulk‐billing incentives for general practitioner visits.20 However, it did not include an increase in income support payments, which remain below the poverty line, despite the Economic Inclusion Advisory Committee’s recommendations.21 In addition, barriers to accessing cost‐of‐living relief measures may exclude many of those who need help most; for example, almost two‐thirds of low income households miss out on energy concessions due to a lack of awareness, and newly arrived migrants can face a waiting period of up to 4 years for support payments.22,23 Future reform is needed to centre support on those experiencing financial disadvantage.

Our policy sentiment analysis reveals very strong public support across all age groups (average, 86.7% [n = 9886]; Supporting Information, supplementary figure 1) for providing additional financial support for families with young children who cannot afford the basics. It is a policy that would help address poverty and material deprivation in the critical first 2000 days of life when the lifelong predictors of chronic disease are established. In addition, major tax reform24 could help reduce financial inequities for families and ensure that the funds required to support children and young people are available.

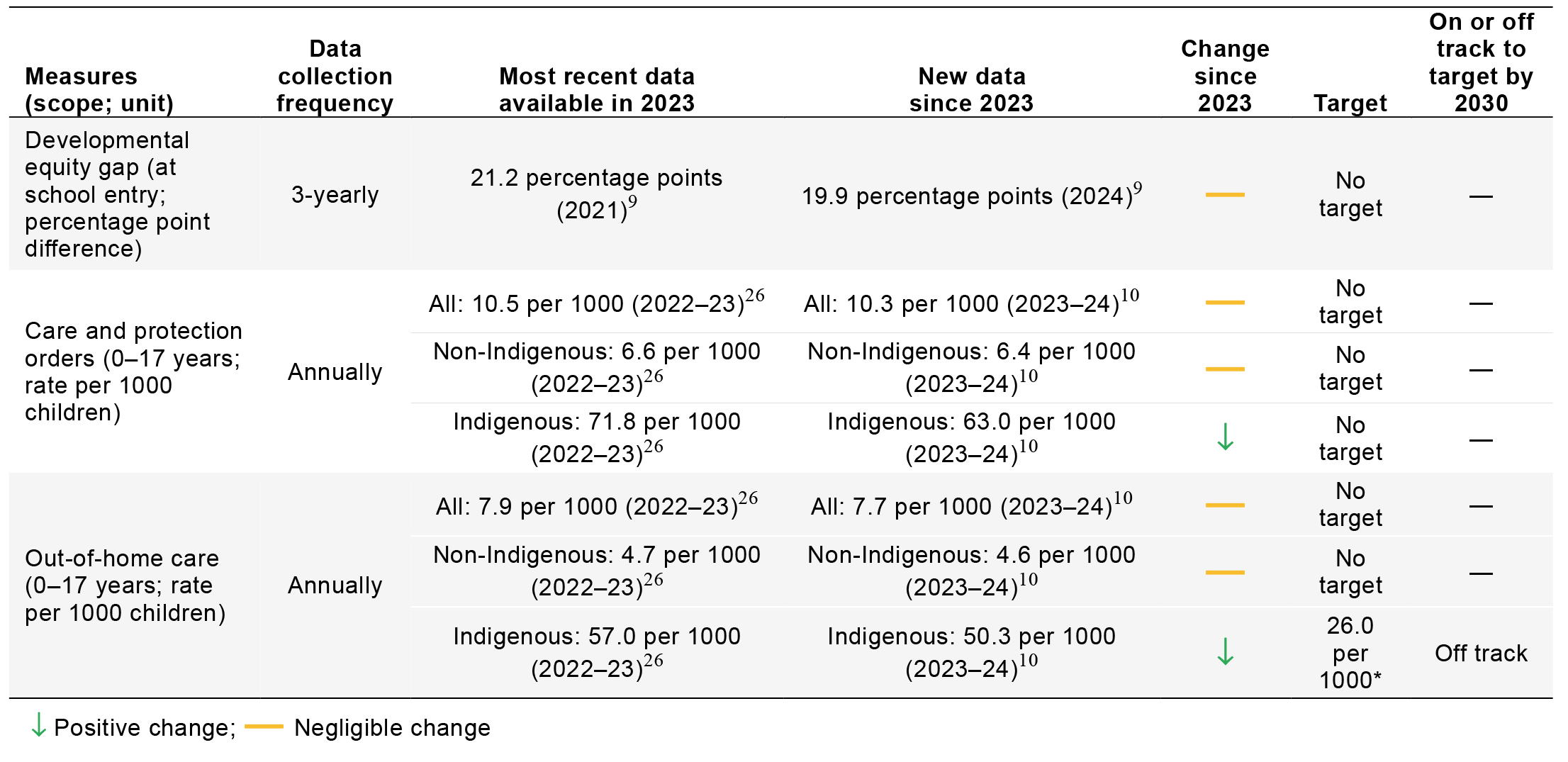

Valued, loved, safe

Children and young people need strong, stable and healthy relationships with family, peers and community to develop and thrive.6 Their safety and development can be supported by a broad range of social services and policies (eg, child and family health services).25 The Australian Early Development Census is a critical marker of whether systems are equitably supporting children in their first 2000 days. Between 2021 and 2024, the developmental equity gap for children who are developmentally vulnerable on one or more domains at school entry narrowed by 1.3 percentage points (Box 5). However, outcomes declined across all socio‐economic groups,9 raising broader, population‐level concerns. Other measures in this domain remain limited.6 Enhancing strengths‐based data measurement, as emphasised in the Early Years Strategy 2024–2034,28 will help improve understanding of this domain for children, young people and their communities, and improve evidence‐based collaboration across systems.

In addition, a nationally consistent measure of adverse childhood experiences, such as abuse, neglect and exposure to family violence,29 is lacking. Current surrogate measures that we rely on are late stage measures of children already experiencing significant critical risk. Some progress has been made since 2022–23 in reducing the continued over‐representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in the child protection system, but rates remain far off track to achieve the Closing the Gap target for out‐of‐home‐care by 2031 (current rate, 50.3 per 1000 children; target rate, 26.0 per 1000 children [Target 12]).27

Sustained, adequately resourced, trauma‐informed and culturally appropriate child and family home visiting services have been shown to play a critical role in improving early development and promoting safe and nurturing environments.30,31 Our policy sentiment analysis reveals very strong public support across all age groups (average, 84.9% [n = 9886]; Supporting Information, supplementary figure 2) for government investment in free home visits delivered by community and health professionals. Yet, investment remains inconsistent, with no clear federal commitment to ensure national access for families experiencing the most disadvantage. At the state and territory level, Queensland committed in 2024 to a statewide rollout of the Maternal Early Childhood Sustained Home‐visiting model for about 3000 families annually,32 while the Northern Territory discontinued funding for the same program.

Positive sense of identity and culture

We looked at the “Positive sense of identity and culture” domain in collaboration with SNAICC — National Voice for our Children. We have integrated their input here with their permission.

Culture is a critical part of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children’s development, identity and self‐esteem and strengthens their overall health and wellbeing. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community‐controlled organisations (ACCOs) have offered holistic early childhood support for decades, going well beyond the mainstream scope of childcare and early education to provide holistic wraparound support for children, extended families and communities. These early learning services are best positioned to provide the services needed to support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children to meet developmental milestones and set them up for success in entering the mainstream education system.33

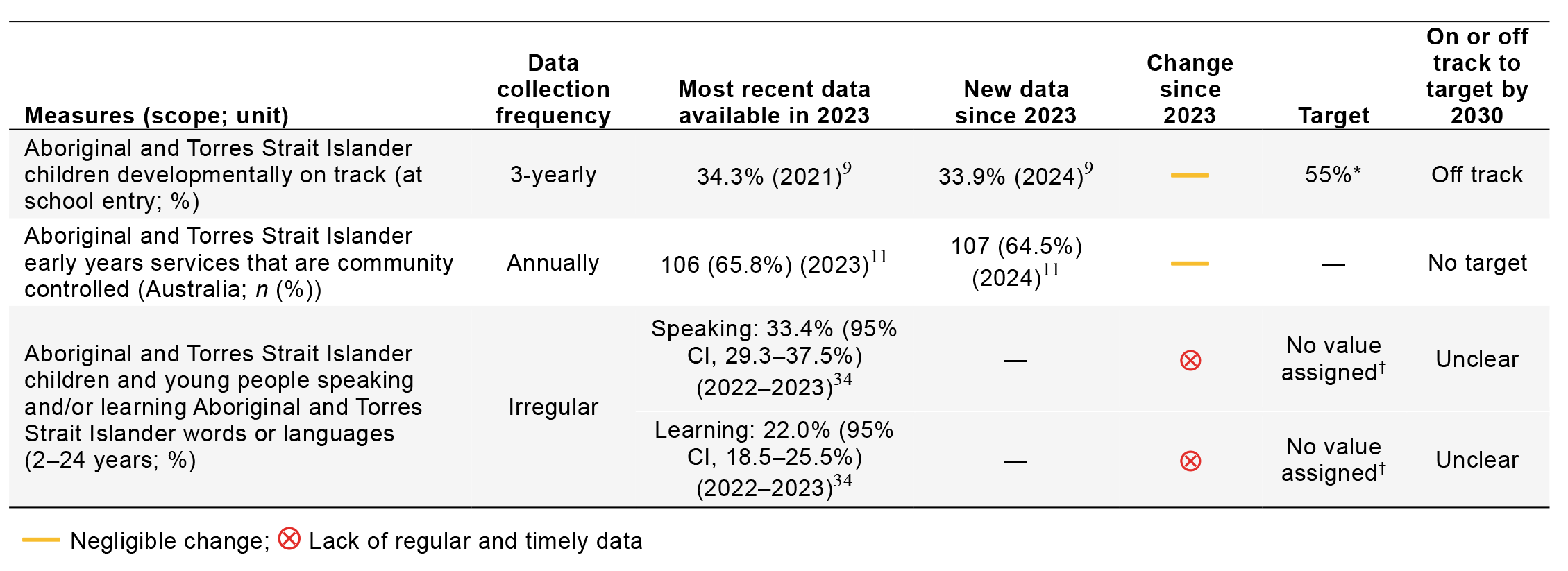

In 2024, 107 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander‐focused early years services (64.5%) were run by ACCOs (Box 6). This has stayed stable since 2023, when 106 services were community controlled (65.8%). Data for 2024 from the Australian Early Development Census show negligible change in the proportion of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander children developmentally on track at school entry, and this measure remains off track for meeting Closing the Gap Target 4.35 There is a dearth of timely and regular data available for the measure of the number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and young people who can speak and/or are learning some words of an Indigenous language. This is a critical measure of culture that should be measured against a clear target to ensure language is passed down across generations.

Funding remains a significant barrier to properly resourcing and increasing the number of ACCO early years services. Reforming the current funding model will enable these services to continue and grow to deliver holistic, wraparound services grounded in culture that support the positive identity, wellbeing and development of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. Our policy sentiment analysis revealed strong public support across all age groups (average, 70.4% [n = 9879]; Supporting Information, supplementary figure 3) for the government to ensure ACCO early years services are properly funded. This is in progress, stewarded by the Early Childhood Care and Development Policy Partnership.37 Implementation advice is currently being drafted for approval by the Early Childhood Care and Development Policy Partnership before going to Australian education ministers.

Healthy

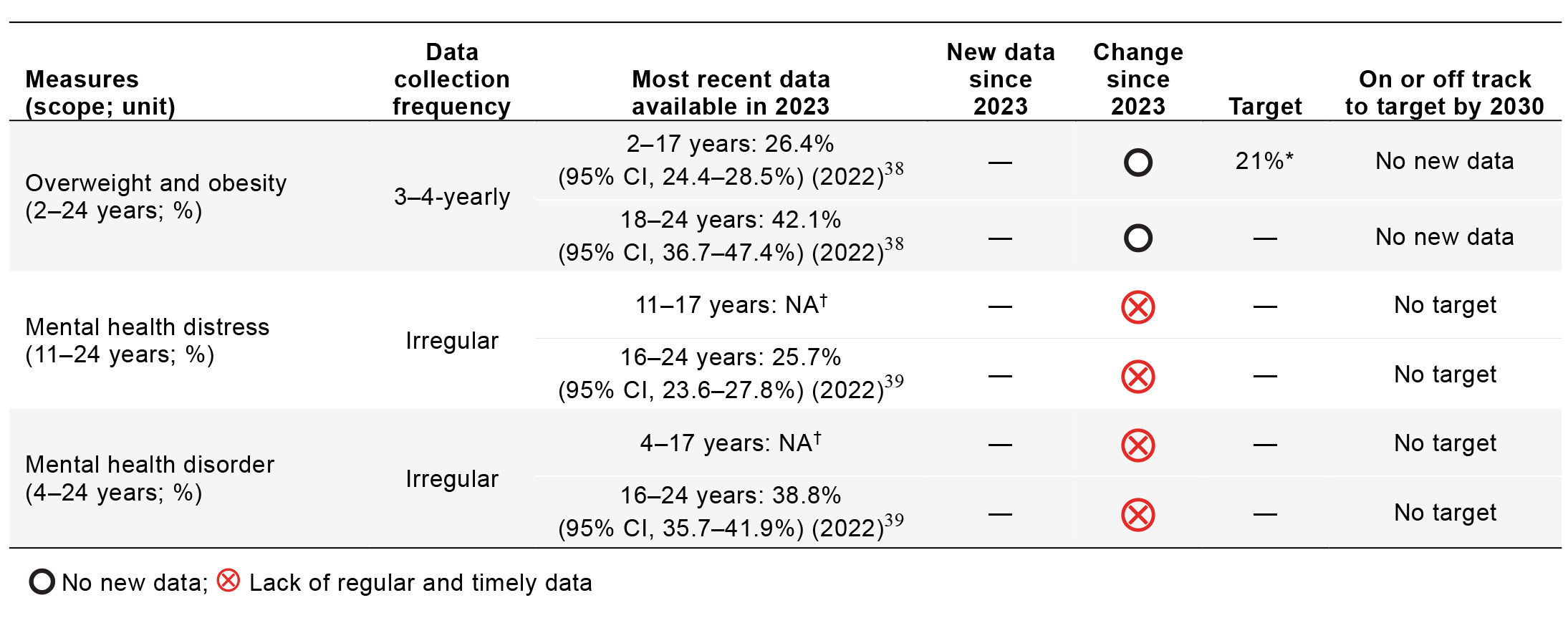

Children and young people need to be physically and mentally healthy to thrive. Baseline data show high rates of overweight and obesity, mental health distress and mental health disorders among children and young people (Box 7). While a national target to reduce the prevalence of overweight and obesity by 5% in 2–17‐year‐olds by 2030 was established in 2022,40 there are no later data from which to assess progress towards this.

Australia lacks the consistent, coordinated measurement systems needed to fully understand the mental health of young Australians.41 The last national child and adolescent mental health survey took place in 2013–14, with results from the next wave not expected until 2027.42 Similarly, mental health data on young adults from the National Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing are sparse, and no future waves of this study are scheduled. Administrative and clinical data are also limited and hard to access, leaving critical gaps in data on emerging health needs and service use.

Physical and mental health outcomes cannot be separated from children and young people’s environments, including their digital environments. They are profoundly shaped by commercial and economic determinants — including the marketing of unhealthy and harmful products such as alcohol, gambling, tobacco and ultra‐processed food.43 Our policy sentiment analysis reveals very strong public support across all age groups (average, 84.6% [n = 9892]; Supporting Information, supplementary figure 4) for protecting children and young people aged under 18 years from the marketing of unhealthy and harmful products. South Australia has recently followed the Australian Capital Territory’s example regarding unhealthy food marketing, with a ban on advertising unhealthy food and drinks on all government‐owned buses, trains and trams that took effect on 1 July 2025.44

At the national level, federal reform in 2024 to restrict the importation, supply and advertising of non‐therapeutic vaping products was introduced after widespread calls from the public health sector.45 However, there has been little appetite for further reform on alcohol, gambling and ultra‐processed food. For example, recommendations from the 2023 parliamentary inquiry (You win some, you lose more)46 to introduce a blanket ban on gambling advertising have not been implemented, despite calls from young people for immediate action.47

Learning and employment pathways

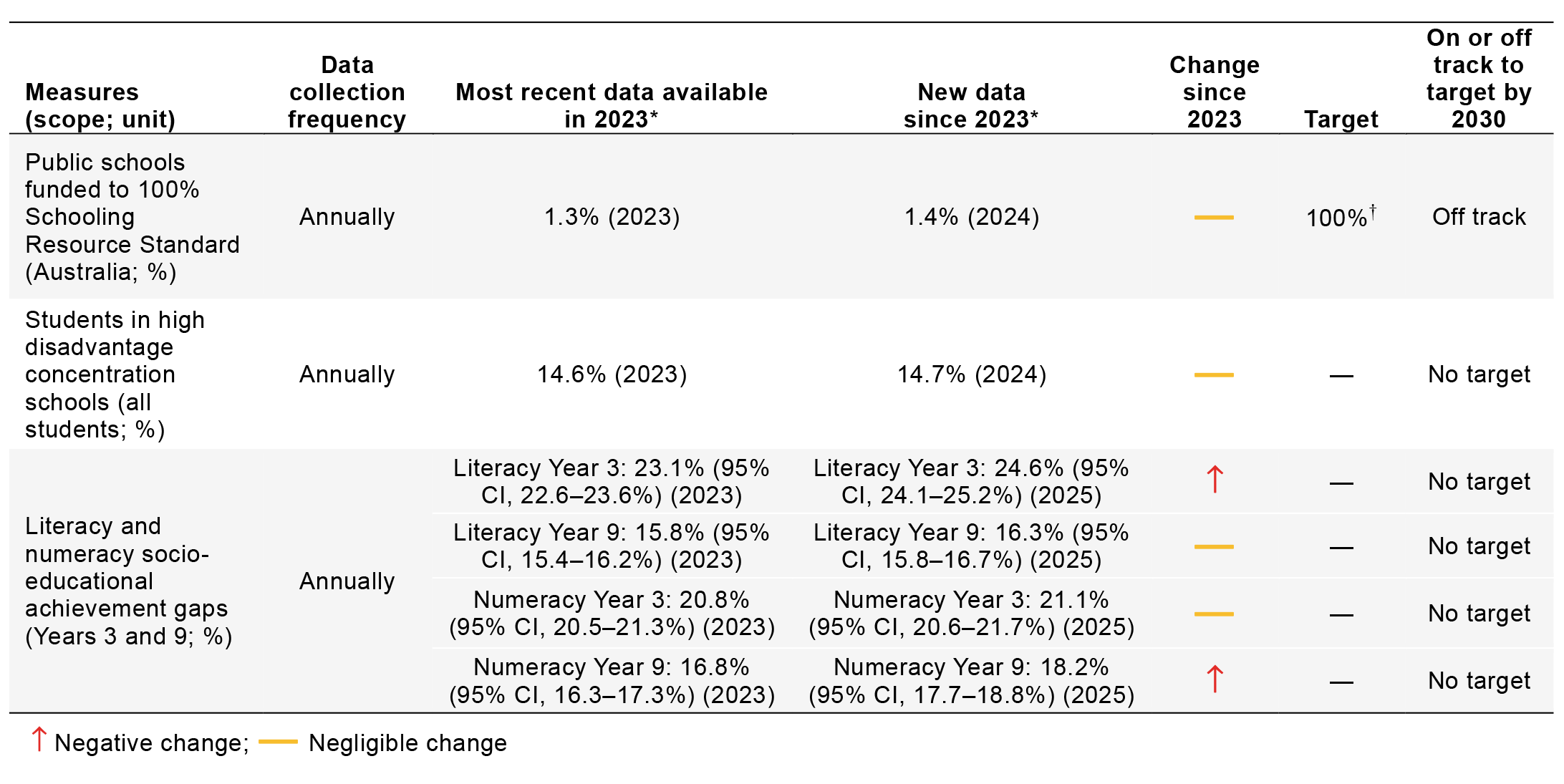

Educational attainment has strong associations with individuals’ life expectancy, morbidity and health behaviour, and is important in shaping their employment and positive trajectory across the life course.48 Equity in education should ensure that all children complete Year 12 or its equivalent, and that students from disadvantaged groups achieve outcomes comparable to their more advantaged peers.49 Yet, public schools in Australia are vastly underfunded in terms of the Schooling Resource Standard, which is an estimate of how much total public funding a school needs to meet its students’ educational needs.50

Data from 2024 show the gap between Australia’s most affluent and most disadvantaged students across the country remains entrenched, with no progress across key measures of education equity (Box 8). The Australian Capital Territory remains the only jurisdiction with fully funded public schools, making up 1.4% of total public schools in the country. The proportion of students attending schools with high concentrations of socio‐educational disadvantage has also remained stable since 2023. In 2025, the literacy achievement gap between the most and least socio‐educationally advantaged students in Year 3 increased (1.5 percentage points), as did the gap for numeracy in Year 9 (1.4 percentage points).

In 2025, the Australian Government committed to ensuring that all public schools receive 100% of their Schooling Resource Standard by 2034 in the Better and Fairer Schools Agreement (2025–2034).51 Securing a pathway to fully fund public schools is a significant win. However, delayed implementation of promised additional funding to public schools risks compounding disadvantage unless funding is rolled out sooner and gives higher priority to the most under‐resourced schools. This approach was strongly backed by the public in our policy sentiment analysis across all age groups (average, 90.3% [n = 9888]; Supporting Information, supplementary figure 5). It is critically important that public schools with high concentrations of socio‐educationally disadvantaged children receive adequate funding without delay. But how additional funding is used is also important. Sustainable solutions to improving equity and excellence in Australian schools require targeted structural investments, including supporting full‐service school models, enhancing family engagement in children’s learning, and subsidising healthy school meal initiatives in public schools.49

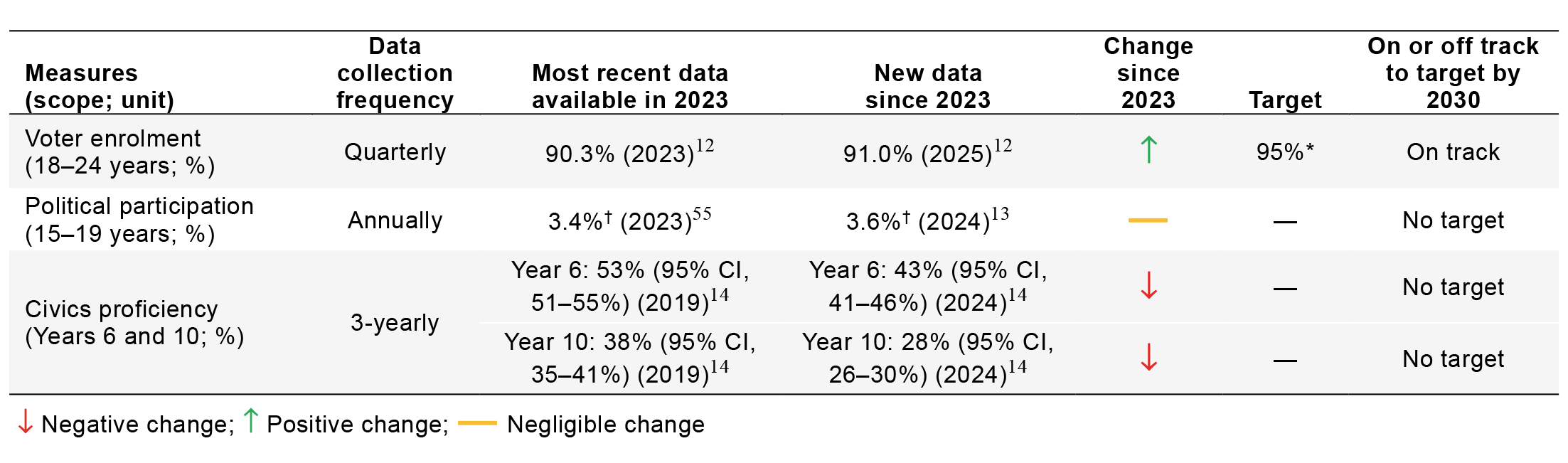

Participating

Children and young people, particularly those from under‐represented communities, have limited power in decision‐making processes.52,53 This weakens the relevance and responsiveness of policies meant to support them. Concurrently, Australia’s education system is failing to prepare young people for civic engagement in democratic decision making — the knowledge and skills needed to participate meaningfully in democratic and political processes.54 Between 2019 and 2024, civics proficiency dropped by 10 percentage points among both Year 6 and Year 10 students, and rates of political participation remained stagnantly low (Box 9). However, there has been a small but notable boost in voter enrolment rates among young Australians in 2025, coinciding with an election year — evidence that young people are interested in having a say in the issues that affect them.

Lowering the voting age to 16 years offers a path to boosting political participation among young people, providing health and wellbeing benefits.57 Our policy sentiment analysis revealed that public support for this remains low in Australia (average, 20.6% [n = 9880]), with notably more support in younger age groups (Supporting Information, supplementary figure 6). Support has increased from the estimate of 6% in 2010,58 and momentum is growing internationally — for example, the United Kingdom has committed to reducing the voting age within the next 4 years.59 Recent commentary from experts in Australia showed near consensus in favour of this reform, particularly when paired with stronger civic and media literacy education for young people.60 Improvements to civics education to support knowledge on voting should be co‐designed with young people, acknowledging their existing interest and stake in politics. Giving them a say in how such education is delivered, along with real‐world responsibilities and learning opportunities outside school, will make it more engaging and effective, especially for those facing structural disadvantage.61

Environments and sustainable futures

A safe, liveable planet is essential to the health and wellbeing of children and young people — now and for generations to come.62 Children are disproportionately at risk from climate change and ecological degradation, and Australia is already experiencing faster‐than‐average warming, with projections pointing to up to a 42‐fold increase in heatwaves by the end of the century.63

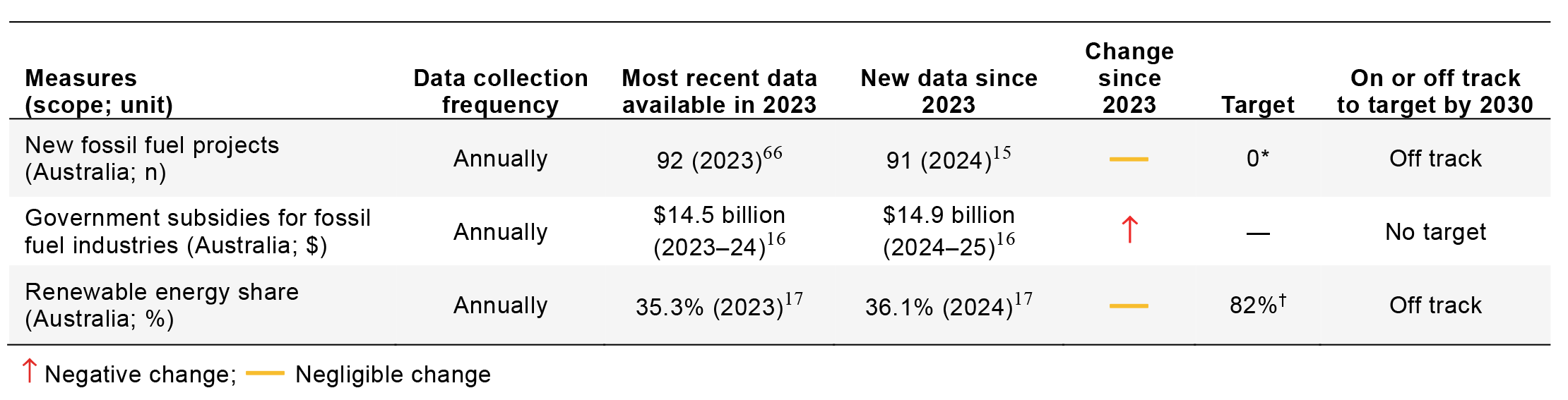

Under the Paris Agreement, the Australian Government has committed to achieving net zero emissions by 2050.64 According to the International Energy Agency, the pathway to net zero should involve no new oil and gas fields, coal mines, or mine extensions approved for development.65 In 2024, 91 new fossil fuel projects were proposed to begin production in Australia (Box 10). The production and use of fossil fuels continue to be promoted in Australia through government subsidies, with federal, state and territory spending and tax breaks for fossil fuel industries increasing by $400 million (2.8%) in 2024–25 from the previous financial year. As part of its plan to transition to net zero, the Australian Government has also committed to achieving 82% renewable energy by 2030.64 The share of energy produced by renewable sources stagnated between 2023 and 2024, and at 36.1% it is off track to meet the agreed national target.

There is a strong call from global and national experts to legislate an immediate end to new fossil fuel developments.65,67,68 Our policy sentiment analysis revealed only moderate public support (average, 44.3% [n = 9858]) for ending new fossil fuel projects, with notably stronger support in younger age groups (Supporting Information, supplementary figure 7). This highlights the need for a stronger understanding of and engagement with public attitudes (eg, fear of more expensive energy) through national leadership, especially among older Australians. A decisive shift in policy direction is critical to ensure a habitable future for young people.

Overarching policy: future generations

Establishing a federal future generations commission with legislated powers to protect the interests of current and future generations would embed intergenerational equity into federal decision making, mirroring Welsh legislation and responding to UN calls for a whole‐of‐government approach to implementing future generations policy.69,70 Our policy sentiment analysis revealed very strong public support across age groups for such policy action (average, 86.9% [n = 9883]; Supporting Information, supplementary figure 8).

In February 2025, the Wellbeing of Future Generations Bill 2025 (Cwlth)71 was introduced into the Parliament of Australia by two members from different political positions, demonstrating the multipartisan support that this work is attracting. This private member’s bill proposes mechanisms to protect the long term wellbeing of current and future generations through a national wellbeing framework; the establishment of a positive duty to consider the interests of future generations; the establishment of a commissioner for future generations; and a mandate for a national conversation to engage citizens in co‐creating a vision for Australia’s future. The introduction of this bill marks a concrete legislative step towards combating the dominance of short term approaches in policy development, and advocacy efforts continue for government adoption of reforms to safeguard the long term wellbeing of current and future generations.

Conclusion

The Countdown will continue to track progress annually, focusing in depth on one of the seven domains shaping the health and wellbeing of children and young people each year. Collectively, annual MJA supplements will lay out the evidence base for action and drive forward a national conversation. The Countdown will act as a tool and a signal: a way to galvanise advocacy and hold decision makers to account for how they choose to value or neglect Australia’s children and young people.

Australia is not yet on track to deliver a fairer, healthier future for its children and young people. Across many of the Countdown’s domains, progress has stalled or is going backwards, and in some areas policy action is absent altogether. Significant data gaps also persist, limiting the visibility of emerging issues and the effectiveness of responses. In addition, we lack many national targets for children and young people’s health and wellbeing, making accountability challenging.

While there have been steps forward, such as progress in commitments for public school funding, their full impact may not be seen for some time. Meaningful change requires long term policy commitment, and the window for action is now. We are in a critical period, and failure to act risks leaving a generation behind. Encouragingly, our sentiment analysis reveals very strong public support for nearly all of the Countdown’s proposed policy actions. This moment demands not only bold leadership, but accountability to the communities calling for change.

Box 1 – Future Healthy Countdown 2030 domains

Source: Reproduced with permission from Lycett et al.4

Box 2 – High level summary of progress in 2025 across Future Healthy Countdown 2030 outcome measures

* Unpublished data provided by the Royal Children’s Hospital National Child Health Poll. † Data that we have calculated; see Supporting Information for details and original data sources.

Box 3 – High level summary of community sentiment towards Future Healthy Countdown 2030 policy actions*

* Results are based on 9858 to 9892 adult respondents, depending on the item.

Box 4 – Material basics: progress across measures

* Unpublished data provided by the Royal Children’s Hospital National Child Health Poll.

Box 5 – Valued, loved, safe: progress across measures

* Closing the Gap Target 12: By 2031, reduce the rate of overrepresentation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children (0–17 years old) in out‐of‐home care by 45% (baseline 2019 rate: 47.3 per 1000 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children).27

Box 6 – Positive sense of identity and culture: progress across measures

* Closing the Gap Target 4: By 2031, increase the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children assessed as developmentally on track in all five domains of the Australian Early Development Census (AEDC) to 55%.35 † Closing the Gap Target 16: By 2031, there is a sustained increase in number and strength of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages being spoken.36

Box 7 – Healthy: progress across measures

NA = not applicable. * One of the goals of the National Obesity Strategy 2022–2032 is to reduce the prevalence of overweight and obesity in 2–17‐year‐olds by at least 5% by 2030.40 † Outdated data from 2013–14 that are unrepresentative of the current population.

Box 8 – Learning and employment pathways: progress across measures

* Data that we have calculated; see Supporting Information for details and original data sources. † Better and Fairer Schools Agreement 2025‐2034: To support all public schools on a path to 100 per cent of the Schooling Resource Standard.51

Box 9 – Participating: progress across measures

* The Australian Electoral Commission aims to ensure that at least 95% of eligible Australians are on the electoral roll at all times, but also has a youth enrolment rate target of 85% for 18–24‐year‐olds.56 We feel that their overall target should be consistent across all age groups.

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- 1. Lycett K, Lane H, Frykberg G, et al. The Future Healthy Countdown 2030 consensus statement: core policy actions and measures to achieve improvements in the health and wellbeing of children, young people and future generations. Med J Aust 2024; 221: S6‐S17. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2024/221/10/future‐healthy‐countdown‐2030‐consensus‐statement‐core‐policy‐actions‐and

- 2. Breadon P. Failure to invest in prevention increases health inequality. Nov 2023. https://grattan.edu.au/news/failure‐to‐invest‐in‐prevention‐increases‐health‐inequality (viewed July 2025).

- 3. SBS News. As high as $7k per student: the funding gaps between private and public schools revealed. SBS News 2024; 6 Sept. https://www.sbs.com.au/news/article/the‐funding‐gap‐between‐private‐and‐public‐school‐students‐revealed/losih77r0 (viewed July 2025).

- 4. Lycett K, Cleary J, Calder R, et al. A framework for the Future Healthy Countdown 2030: tracking the health and wellbeing of children and young people to hold Australia to account. Med J Aust 2023; 219: S3‐S10. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2023/219/10/framework‐future‐healthy‐countdown‐2030‐tracking‐health‐and‐wellbeing‐children

- 5. Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth. What’s in the Nest? Canberra: ARACY, 2024. https://www.aracy.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/2024/10/Whats‐In‐The‐Nest‐2024‐Update.pdf (viewed July 2025).

- 6. Calder R, Dakin P. Valued, loved and safe: the foundations for healthy individuals and a healthier society. Med J Aust 2023; 219: S11‐S14. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2023/219/10/valued‐loved‐and‐safe‐foundations‐healthy‐individuals‐and‐healthier‐society

- 7. Brown N, Azzopardi PS, Stanley FJ. Aragung buraay: culture, identity and positive futures for Australian children. Med J Aust 2023; 219: S35‐S39. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2023/219/10/aragung‐buraay‐culture‐identity‐and‐positive‐futures‐australian‐children

- 8. Rose G. Sick individuals and sick populations. Int J Epidemiol 2001; 30: 427‐432.

- 9. Australian Early Development Census. AEDC national report 2024. Canberra: Department of Education, 2025. https://www.aedc.gov.au/resources/detail/2024‐aedc‐national‐report (viewed Sept 2025).

- 10. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Child protection Australia 2023–24. June 2025. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/child‐protection/child‐protection‐australia‐2023‐24/contents/about (viewed Sept 2025).

- 11. Australian Government Productivity Commission. Number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander early childhood education and care service providers. In: Closing the Gap information repository — socio‐economic area 3: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children are engaged in high quality, culturally appropriate early childhood education in their early years. https://www.pc.gov.au/closing‐the‐gap‐data/dashboard/se/outcome‐area3/aboriginal‐and‐torres‐strait‐islander‐early‐childhood‐education‐and‐care‐service‐providers (viewed Sept 2025).

- 12. Australian Electoral Commission. National youth enrolment rate. Canberra: AEC, 2025. https://www.aec.gov.au/Enrolling_to_vote/Enrolment_stats/performance/national‐youth.htm (viewed Aug 2025).

- 13. McHale R, Brennan N, Boon B, et al. Youth survey report 2024. Sydney: Mission Australia, 2024. https://www.missionaustralia.com.au/publications/youth‐survey (viewed Aug 2025).

- 14. Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority. NAP sample assessments. https://www.acara.edu.au/reporting/national‐report‐on‐schooling‐in‐australia/nap‐sample‐assessments (viewed Aug 2025).

- 15. Department of Industry, Science and Resources. Resources and energy major projects 2024 report. Canberra: Australian Government, 2024. https://www.industry.gov.au/publications/resources‐and‐energy‐major‐projects‐2024 (viewed Aug 2025).

- 16. Grudnoff M, Campbell R. Fossil fuel subsidies in Australia 2025: federal and state government assistance to major producers and users of fossil fuels in 2024–25. Canberra: The Australia Institute, 2025. https://australiainstitute.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/2025/03/P1669‐Fossil‐fuel‐subsidies‐2025‐Web.pdf (viewed Sept 2025).

- 17. Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water. Australian energy statistics, table O: electricity generation by fuel type 2023–24 and 2024. Canberra: Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, 2025. https://www.energy.gov.au/publications/australian‐energy‐statistics‐table‐o‐electricity‐generation‐fuel‐type‐2023‐24‐and‐2024 (viewed Sept 2025).

- 18. Goldfeld SR, Price AM, Al‐Yaman F. Having material basics is basic. Med J Aust 2023; 219: S15‐S19. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2023/219/10/having‐material‐basics‐basic

- 19. Parliament of Australia. Chapter 2 – The extent of poverty in Australia. In: Inquiry into the extent and nature of poverty in Australia: interim report. Canberra: Parliament of Australia, 2023. https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Community_Affairs/PovertyinAustralia/Interim_Report/Chapter_2_‐_The_extent_of_poverty_in_Australia (viewed July 2025).

- 20. Australian Government. Budget 2025–26: cost‐of‐living. https://budget.gov.au/content/01‐cost‐of‐living.htm (viewed July 2025).

- 21. Economic Inclusion Advisory Committee. Economic Inclusion Advisory Committee 2025 report to government. https://www.dss.gov.au/committees/resource/economic‐inclusion‐advisory‐committee‐2025‐report (viewed July 2025).

- 22. Australian Government. 3.1.2.40 Newly arrived resident’s waiting period (NARWP). In: Social security guide, version 1.332. https://guides.dss.gov.au/social‐security‐guide/3/1/2/40 (viewed Sept 2025).

- 23. Botha F, Prakash K. Insights into energy concession awareness and energy‐related behaviours among concession card holders in Australia. Melbourne: Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, 2024. https://melbourneinstitute.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/4971096/Energy‐Charter_Report_Final.pdf (viewed July 2025).

- 24. Spender A. Tax green paper. Sydney: Office of Allegra Spender MP, 2024. https://apo.org.au/node/329119 (viewed July 2025).

- 25. Bird C, Harper L, Muslim S, et al. Exploring the design and impact of integrated health and social care services for children and young people living in underserved populations: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2025; 25: 1359.

- 26. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Child protection Australia 2022–23. July 2024. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/child‐protection/child‐protection‐australia‐insights/contents/insights/supporting‐children (viewed July 2024).

- 27. Australian Government Productivity Commission. Closing the Gap information repository — socio‐economic outcome area 12: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children are not overrepresented in the child protection system. https://www.pc.gov.au/closing‐the‐gap‐data/dashboard/se/outcome‐area12 (viewed Sept 2025).

- 28. Australian Government. Early Years Strategy 2024–2034. Canberra: Department of Social Services, 2024. https://www.dss.gov.au/early‐years‐strategy/resource/early‐years‐strategy‐2024‐2034 (viewed Sept 2025).

- 29. Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med 1998; 14: 245‐258.

- 30. Kildea S, Gao Y, Hickey S, et al. Effect of a Birthing on Country service redesign on maternal and neonatal health outcomes for First Nations Australians: a prospective, non‐randomised, interventional trial. Lancet Glob Health 2021; 9: e651‐e659.

- 31. Goldfeld S, Bryson H, Mensah F, et al. Nurse home visiting to improve child and maternal outcomes: 5‐year follow‐up of an Australian randomised controlled trial. PLoS One 2022; 17: e0277773.

- 32. Miles S, Fentiman S. Miles government investment to put more Townsville kids first, with help at home [media statement]. 5 June 2024. Queensland Government. https://statements.qld.gov.au/statements/100494 (viewed July 2025).

- 33. SNAICC. Funding model options for ACCO integrated early years services: final report. Canberra: SNAICC, 2024. https://www.snaicc.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/2024/05/240507‐ACCO‐Funding‐Report.pdf (viewed July 2024).

- 34. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Microdata and TableBuilder: National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey, Australia. Sept 2025. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/microdata‐tablebuilder/available‐microdata‐tablebuilder/national‐aboriginal‐and‐torres‐strait‐islander‐health‐survey‐australia (viewed Sept 2025).

- 35. Australian Government Productivity Commission. Closing the Gap information repository — socio‐economic outcome area 4: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children thrive in their early years. https://www.pc.gov.au/closing‐the‐gap‐data/dashboard/se/outcome‐area4 (viewed Sept 2025).

- 36. Australian Government Productivity Commission. Closing the Gap information repository — socio‐economic outcome area 16: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures and languages are strong, supported and flourishing. https://www.pc.gov.au/closing‐the‐gap‐data/dashboard/se/outcome‐area16 (viewed Sept 2025).

- 37. Department of Education. Early Childhood Care and Development Policy Partnership. https://www.education.gov.au/closing‐the‐gap/closing‐gap‐early‐childhood/early‐childhood‐care‐and‐development‐policy‐partnership (viewed Sept 2025).

- 38. Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Health Survey. Dec 2023. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/health‐conditions‐and‐risks/national‐health‐survey/latest‐release (viewed Aug 2025).

- 39. Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Oct 2023. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/mental‐health/national‐study‐mental‐health‐and‐wellbeing/latest‐release (viewed July 2024).

- 40. Health Ministers’ Meeting. National Obesity Strategy 2022–2032. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2022. https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/national‐obesity‐strategy‐2022‐2032 (viewed July 2024).

- 41. Lycett K, Frykberg G, Azzopardi PS, et al. Monitoring the physical and mental health of Australian children and young people: a foundation for responsive and accountable actions. Med J Aust 2023; 219: S20‐S24. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2023/219/10/monitoring‐physical‐and‐mental‐health‐australian‐children‐and‐young‐people

- 42. Curtin University. Young Minds: Our Future. https://research.curtin.edu.au/young‐minds‐our‐future (viewed July 2025).

- 43. Gilmore AB, Fabbri A, Baum F, et al. Defining and conceptualising the commercial determinants of health. Lancet 2023; 401: 1194‐1213.

- 44. Preventative Health SA. Unhealthy food and drink ads now banned on government owned buses, trains and trams in South Australia [media release]. 1 July 2025. https://www.preventivehealth.sa.gov.au/about/news‐announcements/public‐transport‐unhealthy‐food‐and‐drink‐ad‐ban‐now‐in‐effect (viewed Sept 2025).

- 45. Australian Council on Smoking and Health. ACOSH is calling on all politicians to support the vaping reform bill. https://acosh.org/advocacy‐priorities/vapefree (viewed July 2025).

- 46. House of Representatives Standing Committee on Social Policy and Legal Affairs. You win some, you lose more. Inquiry into online gambling and its impacts on those experiencing gambling harm: report. June 2023. https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/House/Social_Policy_and_Legal_Affairs/Onlinegamblingimpacts/Report (viewed July 2025).

- 47. Pitt H, McCarthy S, Randle M, et al. “It’s changing our lives, not for the better. It’s important that we have a say”. The role of young people in informing public health and policy decisions about gambling marketing. BMC Public Health 2024; 24: 2004.

- 48. Sahlberg P, Goldfeld SR. New foundations for learning in Australia. Med J Aust 2023; 219: S25‐S29. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2023/219/10/new‐foundations‐learning‐australia

- 49. Sahlberg P, Cobbold T. What fully funded public schools could do. Med J Aust 2025; 223 (9 Suppl): S17‐S21.

- 50. Department of Education. Schooling Resource Standard. https://www.education.gov.au/recurrent‐funding‐schools/schooling‐resource‐standard (viewed July 2024).

- 51. Department of Education. The Better and Fairer Schools Agreement (2025–2034). https://www.education.gov.au/recurrent‐funding‐schools/national‐school‐reform‐agreement/better‐and‐fairer‐schools‐agreement‐20252034 (viewed July 2025).

- 52. Kapeke K, Muse K, Rowan J, et al. Who holds power in decision making for young people’s future? Med J Aust 2023; 219: S30‐S34. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2023/219/10/who‐holds‐power‐decision‐making‐young‐peoples‐future

- 53. Cory J, Kuchel H, Dukakis B, et al. Participation of Indigenous children and young people to improve health and wellbeing. Med J Aust 2024; 221: S26‐S33. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2024/221/10/participation‐indigenous‐children‐and‐young‐people‐improve‐health‐and‐wellbeing

- 54. Collin P. Australian students just recorded the lowest civics scores since testing began. But young people do care about politics. The Conversation, 18 Feb 2025. https://theconversation.com/australian‐students‐just‐recorded‐the‐lowest‐civics‐scores‐since‐testing‐began‐but‐young‐people‐do‐care‐about‐politics‐250047 (viewed July 2025).

- 55. McHale R, Brennan N, Freeburn T, et al. Youth survey report 2023. Sydney: Mission Australia, 2023. https://www.missionaustralia.com.au/publications/youth‐survey (viewed July 2024).

- 56. Australian Electoral Commission. Enrolment program performance indicators and targets. July 2022. https://www.aec.gov.au/Enrolling_to_vote/Enrolment_stats/performance (viewed Sept 2025).

- 57. Kapeke K, Saw P, Krutsch E, et al. Young voices, healthy futures: the rationale for lowering the voting age to 16. Med J Aust 2024; 221: S18‐S22. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2024/221/10/young‐voices‐healthy‐futures‐rationale‐lowering‐voting‐age‐16

- 58. McAllister I. The politics of lowering the voting age in Australia: evaluating the evidence. Aust J Polit Sci 2014; 49: 68‐83.

- 59. Morton B, Smith A, Awomoyi J. Voting age to be lowered to 16 by next general election. BBC News 2025; 18 July. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c628ep4j5kno (viewed July 2025).

- 60. Petter P, Williams B, Gordon F, et al. Should Australia lower the voting age to 16 like the UK? We asked 5 experts. The Conversation 2025; 23 July. https://theconversation.com/should‐australia‐lower‐the‐voting‐age‐to‐16‐like‐the‐uk‐we‐asked‐5‐experts‐261469 (viewed July 2025).

- 61. Ghazarian Z, Laughland‐Booy J, De Lazzari C, Skrbis Z. How are young Australians learning about politics at school?: the student perspective. J Appl Youth Stud 2020; 3: 193‐208.

- 62. Sly PD, Stanley FJ. Sustainable environments for Australian children’s and young people’s health and wellbeing: our young’s welfare is threatened. Med J Aust 2023; 219: S40‐S43. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2023/219/10/sustainable‐environments‐australian‐childrens‐and‐young‐peoples‐health‐and

- 63. Nishant N, Ji F, Guo Y, et al. Future population exposure to Australian heatwaves [letter]. Environ Res Lett 2022; 17: 064030.

- 64. Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water. Australia’s Net Zero Plan. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2025. https://www.dcceew.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/net‐zero‐report.pdf (viewed Sept 2025).

- 65. International Energy Agency. Net zero by 2050: a roadmap for the global energy sector. Paris: IEA, 2021. https://www.iea.org/reports/net‐zero‐by‐2050 (viewed June 2024).

- 66. Department of Industry, Science and Resources. Resources and energy major projects 2023 report. Canberra: Australian Government, 2023. https://www.industry.gov.au/publications/resources‐and‐energy‐major‐projects‐2023 (viewed June 2024).

- 67. United Nations Environment Programme. Governments’ fossil fuel production plans dangerously out of sync with Paris limits. Oct 2021. https://www.unep.org/news‐and‐stories/press‐release/governments‐fossil‐fuel‐production‐plans‐dangerously‐out‐sync‐paris (viewed June 2024).

- 68. The Australia Institute. No new fossil fuel projects [open letter]. https://nb.australiainstitute.org.au/scientists_open_letter (viewed June 2024).

- 69. Future Generations Comissioner for Wales. Well‐being of Future Generations Act 2015. https://futuregenerations.wales/discover/about‐future‐generations‐commissioner/future‐generations‐act‐2015 (viewed July 2025).

- 70. United Nations. Declaration on Future Generations. https://www.un.org/en/summit‐of‐the‐future/declaration‐on‐future‐generations (viewed July 2025).

- 71. Parliament of Australia. Wellbeing of Future Generations Bill 2025. https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Bills_Legislation/Bills_Search_Results/Result?bId=r7315 (viewed July 2025).

This article is part of a supplement that was funded by the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation (VicHealth). VicHealth is a pioneer in health promotion. It was established by the Parliament of Victoria as part of the Tobacco Act 1987 (Vic) and has a primary focus on promoting good health for all and preventing chronic disease. We acknowledge and thank SNAICC — National Voice for our Children for their contribution to parts of this article.

No relevant disclosures.

Author contributions:

Georgie Frykberg: Conceptualization, formal analysis, writing – original draft, writing – reviewing and editing. Angelica Ojinnaka‐Psillakis: Conceptualization, writing – reviewing and editing. Planning Saw: Conceptualization, writing – reviewing and editing. Kevin Kapeke: Writing – reviewing and editing. Cham Kim: Writing – reviewing and editing. Amie Furlong: Writing – reviewing and editing. Susan Maury: Writing – reviewing and editing. Anna Price: Writing – reviewing and editing. Peter Sly: Writing – reviewing and editing. Taylor Dee Hawkins: Writing – reviewing and editing. Khalid Muse: Writing – reviewing and editing. Pasi Sahlberg: Writing – reviewing and editing. Prue Warrilow: Writing – reviewing and editing. Fiona Stanley: Writing – reviewing and editing. Jordan Cory: Writing – reviewing and editing. Carolyn Wallace: Writing – reviewing and editing. Adam Valvasori: Writing – reviewing and editing. Ngiare Brown: Writing – reviewing and editing. Craig Olsson: Writing – reviewing and editing. Yichao Wang: Formal analysis, writing – reviewing and editing. Sharon Goldfeld: Conceptualization, writing – reviewing and editing. Rosemary Calder: Conceptualization, writing – reviewing and editing. Kate Lycett: Conceptualization, writing – reviewing and editing.