The known: Narrow forms of learner recognition limit definitions of educational success. This is exacerbated for First Nations learners, who have historically and systematically been excluded by education systems.

The new: Agreements between Indigenous Nations and schools that operate on their Country create a foundation of shared custodianship for learners that centres the wellness of the Indigenous learner as a whole being.

The implications: The Indigenous Nation‐led learning charter model that we developed sets the aspirations for all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander learners learning on a specific Country. It provides guidance and leadership in partnership with schools that centres First Nations learners.

First Nations learners navigate education systems, constructed as part of settler‐colonial nation‐building effort, that have historically and systematically excluded First Nations peoples’ cultures, languages and knowledge systems from the classroom.1 This history of exclusion has excluded the voices and learning ambitions defined by First Nations young people, families and communities. Contemporary policy approaches such as Closing the Gap have come to define success in First Nations education narrowly — aligning metrics to achieving parity with non‐Indigenous Australians, while increasing literacy, numeracy and attendance — and overlook skills and knowledges valued by First Nations people.2 The practice of skills and knowledges embedded in cultural learning is how First Nations knowledges thrive intellectually and physically. This article asserts First Nations young people as whole learners, and this position is critical to their health and wellbeing.3

Education justice requires defining success on First Nations’ terms, aligning with interconnected pursuits for land, child rearing and cultural revitalisation.4 The National Indigenous Youth Education Coalition articulates this as “Success as First Nations” —“Our measures of success are based on the history, values and aspirations of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people and communities, and which supports their future pathways in learning and life”.5 Defining learning on First Nations’ terms means recognising Indigenous justice pursuits that are social, economic and political in nature, all of which reinforce and align with cultural determinants of social and emotional wellbeing.

A key example of this is First Nations child‐rearing practices that emphasise the importance of learning when deemed appropriate by families and communities, reflecting distinct pedagogies and values. These forms of learning are foundational, not supplementary, and are integral to identity, belonging, and intergenerational knowledge transmission. They contribute to the overall healthy development of children by teaching geographical boundaries of Country, places and practices to retrieve plants for medicinal and ceremonial purposes, and knowledge and respect for previous generations — all of which develop protective factors for young people. Where such pedagogies are sidelined in favour of system‐defined metrics, this incurs a cost — cultural, social and emotional — borne disproportionately by First Nations learners and communities, across generations.

Vital to this reality is acceptance that First Nations communities set ambitions for their young people as members of collective societies. First Nations learning ambitions embody Indigenous self‐determination and are practised across the continent of Australia.6 While these learning ambitions have survived ongoing colonisation, they are not articulated at a system level.7

This study is part of a broader project, the Learning Creates Australia Learner’s Journey Social Lab, and is aimed at redesigning learner recognition systems to value the knowledges and skills of First Nations students.8 The goal is not to lower academic standards but to renegotiate the relationships between schools and communities, recognising the interconnectedness of education, community and Country.

The Learning Creates Australia First Nations team consisted entirely of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, including the two of us as First Nations co‐convenors (HM, MM), First Nations multidisciplinary collaborators, and a community‐based partnership with the Darumbal People Aboriginal Corporation.9 The task was to develop prototypes for broader recognition of learning success of First Nations young people. The work ultimately led to the development of an Indigenous Nation‐led learning charter (ie, set of core principles identified by a specific traditional owner group) that centres the recognition of First Nations learner wellbeing. An embedded self‐determined First Nations leadership model was critical to this work and included a foundational partnership with the National Indigenous Youth Education Coalition.

This work acknowledges that the future is an exciting and rapidly changing one which requires young people to develop mixes of social, cognitive, emotional and knowledge skills to prepare them for post‐school pathways as well as community roles and responsibilities. However, marginalised children and young people are disengaging from the broad education system and have been suffering the consequences of disengagement for years already. This article is part of the 2025 MJA supplement for the Future Healthy Countdown 2030,10 which examines how learning and employment pathways affect the health and wellbeing of children, young people, and future generations, in our case Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and young people.

Methods

Setting, study design and procedure

The Learner’s Journey Social Lab was conducted over a 12‐month period, from 1 October 2020 to 31 October 2021. A social lab creates research settings where experts and stakeholders can collaborate and experiment to develop actionable solutions that address complex societal challenges. The Learners Journey Social Lab was focused on broadening Australia’s learner recognition system to create better and fairer pathways for all young people. The First Nations‐specific social lab was one of five social labs. It was selected to conduct the groundwork for the project because of its iterative co‐design approach, its ability to position learners at the centre of the work, and its capacity to draw on the experiences of those most impacted by the problem.

The First Nations team determined the principles, values and direction of the project in alignment with Indigenous worldviews and agreed to work with shared commitment to community accountability. They employed a method that was underpinned by the rights of Indigenous peoples as set out by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. This way of operating would not have been possible without Indigenous people insisting on their rights to self‐determination throughout all stages of the social lab and continuously grounding the work in Country. Three key lines of inquiry emerged iteratively from co‐design within the First Nations‐specific social lab team:

- understanding First Nations learner journeys;

- cultural determinants of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social and emotional wellbeing to broaden recognition of learning success; and

- First Nations sovereignty and self‐determination: exploring custodianship of learning.

The First Nations team iteratively built on the insights gained through a series of interviews and yarns with stakeholders to develop a prototype that responded to these lines of inquiry, and the broader focus of the Learner’s Journey Social Lab of shifting the learner recognition system. This work is reported according to the standards for reporting qualitative research (Supporting Information).11

Participants

The First Nations research team employed a focus group and interviews with First Nations young people, alongside stakeholder engagement and co‐design conversations. A collaborative yarning approach was used to both generate and share emergent insights, while iteratively incorporating feedback from a wider network of First Nations education stakeholders, including educators, representatives from community‐controlled organisations, allied health professionals, policy makers, and academics. Participants were recruited through the diverse networks of the First Nations research team and partners involved in the social lab. Eligibility for the focus group and the interviews was based on Indigenous status and age, with a focus on those currently in high school or who had recently left school. Demographic information collected was limited to Indigenous status, age range, and professional sector.

Ethics approval

This research was approved by the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Research Ethics Committee (reference EO225‐20201116).

Governance

The First Nations team led a self‐determined co‐design process within the team led by First Nations co‐convenors. Senior First Nations experts acted as champions who provided guidance and support through the social lab. The First Nations team adopted a relational approach that focused on building trust with community, stakeholders and team members through methods of shared decision making, co‐design, iterative feedback and accountability. These arrangements moved beyond procedural oversight to embed relational ethics at the core of the social lab process.12

Data analysis

Participants and parents or guardians were provided with written information sheets clearly stating the aim, objectives and process for the focus group and the interviews as well as a consent form for participants and guardians. Interviews were recorded via videoconferencing facilities. The focus group was conducted in person with members of the First Nations team. Focus group data were collated using an Indigenous learner journey map, developed by the First Nations team, which was completed through a facilitated conversation with the First Nations team members. A thematic analysis was applied to collected data by identifying keywords and categories of issues discussed by participants. The First Nations team deliberated over recordings, keywords and categories as a collaborative group and to use each other’s expertise to consider the data.

Results

The First Nations research team conducted a focus group with 17 First Nations high school students aged 14–17 years, as well as four interviews with First Nations young people aged 18–25 years. In addition, the team engaged 51 stakeholders through a series of collaborative yarns. Collectively, these activities informed the design of the First Nations‐led learning charter model.

Inquiry line 1 — understanding First Nations learner journeys

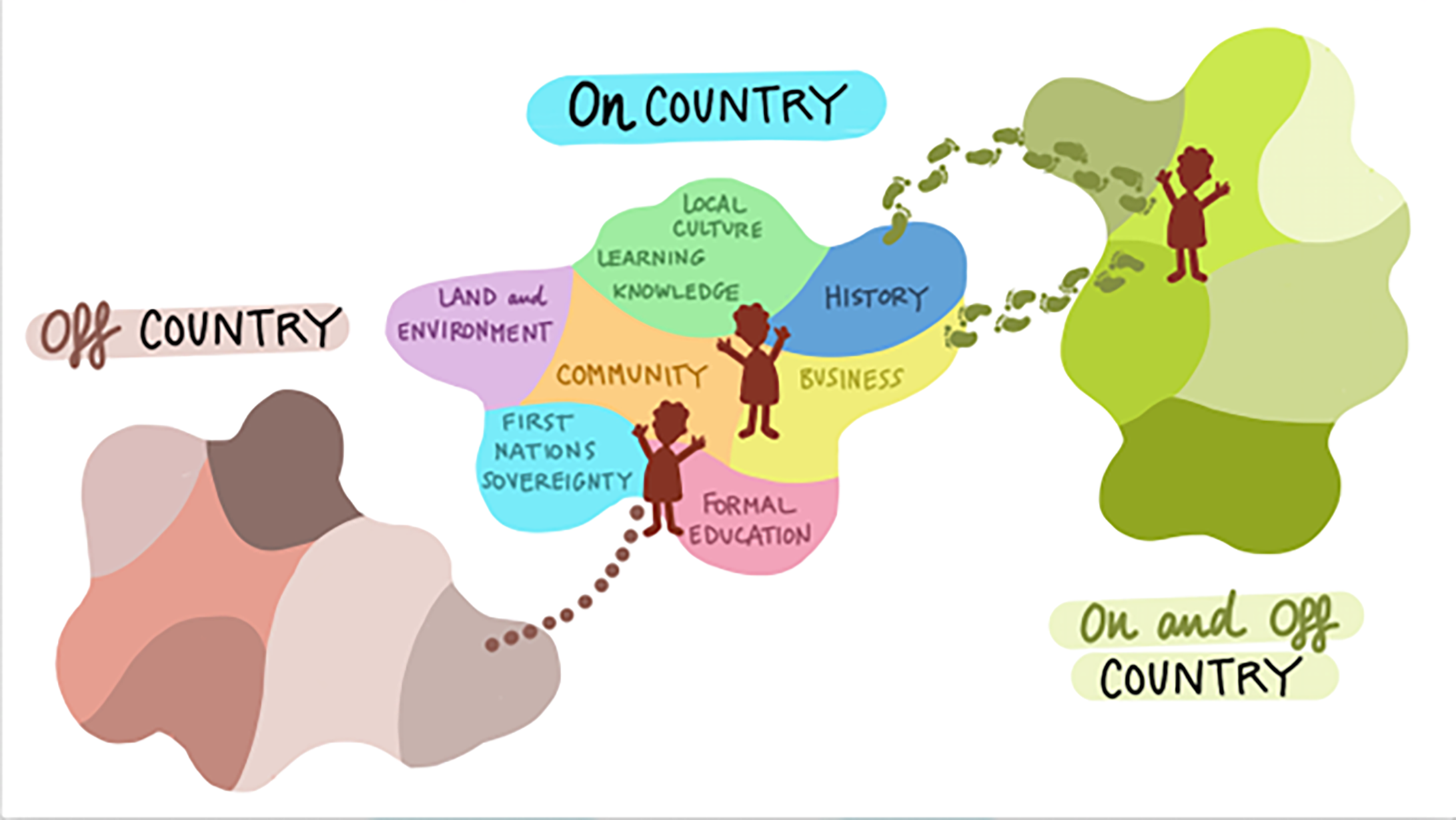

The First Nations team developed a high level conceptual framework to examine the diverse learning journeys of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students and young people, informed by their distinct and context‐specific relationships to the lands on which they live and learn.

The conceptual framework outlined three broad learning journeys of the Indigenous learner (Box 1):

- learners living off Country (living and learning on another Nations’ custodial lands);

- learners staying on Country (living and learning on their custodial lands); and

- learners travelling back and forth (living and learning in different locations but consistently travelling back and forth, including those travelling on and off Country).

The framework was premised on the context of learning that can occur within the site, or boundary, of an Indigenous Nation. Indigenous Nations hold custodianship over their Country, languages, knowledge systems and cultures. Organised through systems of governance and cultural authority, they are political entities capable of negotiating their arrangements with settler‐colonial states and institutions.13 The framework layers the learning journey that occurs as young people navigate and move through their different learning experiences, drawing on the different relationships they hold to place, to community and to local custodians. It recognises that different learning journeys can all exist simultaneously within the bounds of an Indigenous Nation, and that a First Nations young person may embody different learning journeys across their learning life.

Thematic analysis of youth focus group and interviews

A thematic analysis of the stories shared by young people through the interviews and the focus group identified key learning ambitions and challenges across the different learning journeys. These are presented in Box 2.

The story in Box 3 presents an example of an individual learning journey from a recent high school graduate aged 18 years. Collected through an individual interview, it provides a deeper insight into the agency that First Nations students are demonstrating to balance the requirements of formal education systems, while also pursuing learning ambitions connected to their culture and identity as a First Nations person.

Rigney (2021) describes First Nations learners as “competent subjects and experts of their life‐worlds, capable of producing knowledge for improving their lives and those of their communities”.6 As in the case of the learning journey provided in Box 3 the First Nations learner is capable of and competent in implementing the strategies needed to access the skills and knowledges that they value for their sense of identity, belonging, and future employment and education pathways. The family played a critical role in endorsing and encouraging the learning ambitions of the student, although this was not valued or recognised by the school. Central to this experience is the care for the student’s wellbeing. The family recognised the importance of being connected to language and Country and facilitated opportunities for the student to access this education.

Inquiry line 2 — cultural determinants of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social and emotional wellbeing to broaden recognition of learning success

It became clear through the data analysis that young people were advocating for their own wellbeing at the relationship between ambitions and challenges and that this was fundamental to any work interested in broadening the recognition of learning for First Nations learners. Wellbeing in this context is defined by all the components of Indigenous cultures that make Indigenous children and young people well. The First Nations prototyping team consulted with Indigenous health researchers to better understand Indigenous wellbeing. From these consultations, the cultural determinants of wellbeing model developed by the National Strategic Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples’ Mental Health and Social and Emotional Wellbeing 2017–2023 and the Mayi Kuwayu Study were adopted.

Inquiry line 3 — First Nations sovereignty and self‐determination: exploring custodianship of learning

The First Nations student as a “valuer” in their own learning journey identified, as outlined in Box 2, their learning ambitions; these included learning about Country, culture, and community expectations. This learning is all that exists within the context of family and community and is underpinned by the sovereignty and custodial rights of the local First Nation. In shifting who we view as the “valuer”, we also shift how we define meaningful learning. In this project, it was identified that what was valued by First Nations young people aligned with their cultural determinants of wellbeing, not just further learning or employment pathways.

First Nations knowledge systems stem from our connection to land (Country). It is this relationship to Country that provides the foundation for which our laws, cultures, decision making and sovereignty are expressed.14 Contemporary pursuits for land rights, like native title, identified the connection between learning and land. First Nations people advocated for a social justice package to be delivered alongside the native title legislation, aimed at supporting First Nations citizenry rights to education.15 While it is argued that First Nations agreed to native title, based on the social justice measures, the proposed package was never honoured by the federal government.16

It is therefore inadequate to view neoliberal education systems introduced through the process of colonisation as the arbiter of learning, or to assume that all learning that is valued by First Nations people should be (and could be) facilitated by these same neoliberal systems.17 To do so dismisses the roles that families, communities and Country play as educators. However, in such neoliberal societies, like Australia, it is typically learning that is tested and credentialed through formal education systems that is validated. Shifting who we view as the “valuer” of learning enables us to broaden what learning is happening and who plays a role in that learning.

Introducing a model for Indigenous Nation‐led learning charters

Drawing from the emerging themes from the interviews and the focus group, a set of design principles was developed to underpin the creation of the prototype — a model for an Indigenous Nation‐led learning charter. The design principles included:

- First Nations sovereignty underpins the context for learning — sovereignty that is innately connected to land and expressed through relationships and responsibilities to honour custodial ethics and obligations.18

- First Nations young people identified a broader set of learning ambitions, where they can feel proud and strong in who they are without having to sacrifice any parts of their cultural identity, wellbeing or strengths.

- Schools facilitate learning and education on the lands of Indigenous Nations.

These design principles require a broadened understanding of who plays a role in the value and recognition of learning. Indeed, this role is shared among students and families, schools, and custodians who hold collective ambitions for learning and education on their lands. While the roles were clear, how these relationships were negotiated demonstrated a difference of power, complicated by differing views, expectations and values of educational success.

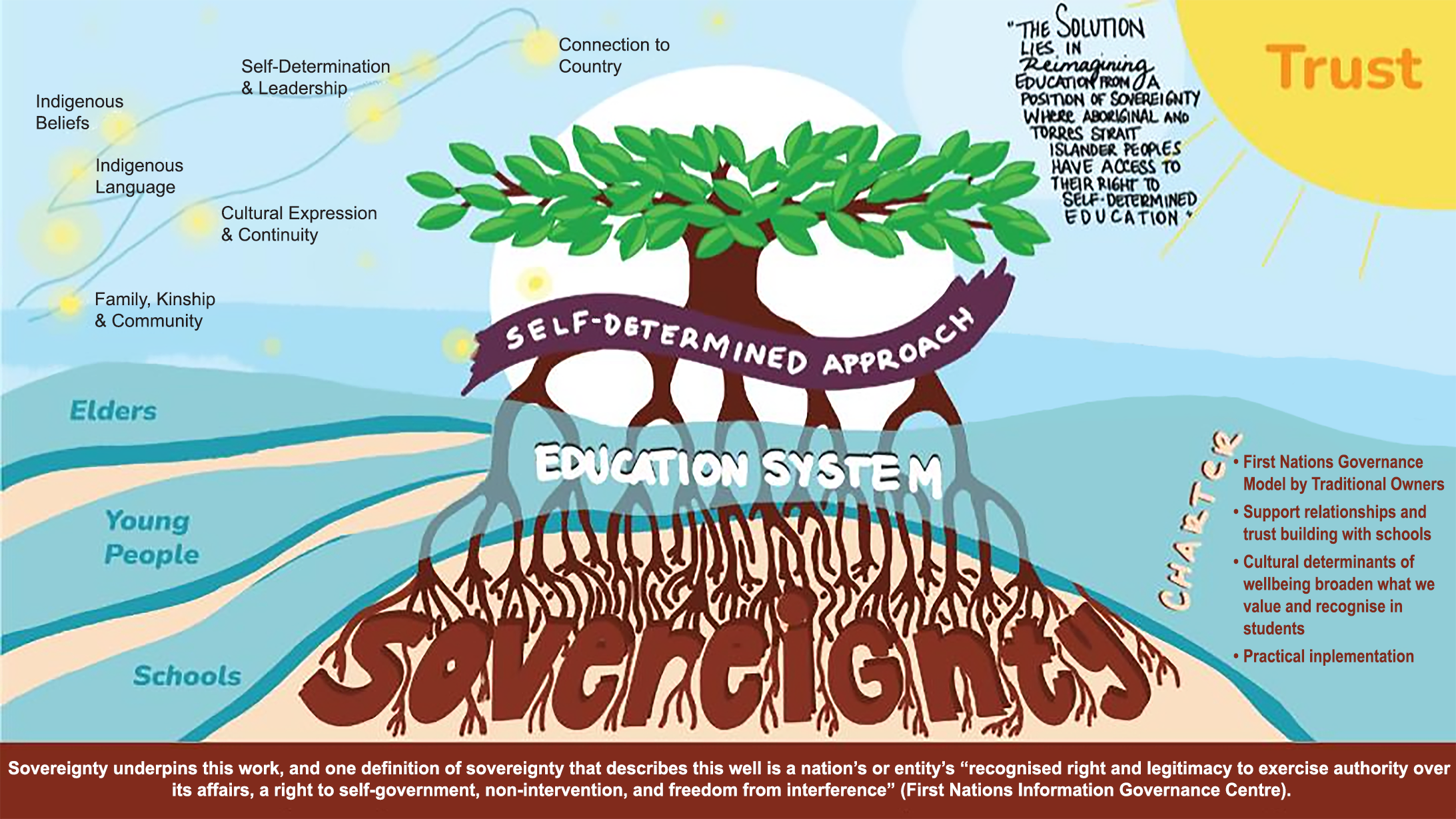

In response to this, a model for an Indigenous Nation‐led learning charter was developed as a prototype to renegotiate the relationships between schools and traditional custodians centred around valuing and recognising the wellbeing of First Nations students. A visual representation of the charter is provided in Box 4. The team deliberately chose to use a charter model, drawing on existing charter agreements,20 as the foundation for the prototype to provide a common framework to establish relationships, set expectations and guide collective action.

Discussion

Indigenous‐led learning charters express First Nations learning ambitions. They are defined principally by traditional custodians and provide opportunities to renegotiate relationships. The charter model that we developed establishes a renewed foundation to reform relationships that guide cooperation, centred around the learner. Importantly, it positions all schools as custodians of Indigenous learners’ belonging and wellbeing. The charter promotes the enabling conditions by developing best practice partnerships where young people are supported to connect with and express their sense of self and identity. The result is an increased belonging that supports young people’s engagement and agency in learning — inside and outside of the classroom, recognising who they are, what they can do and where they connect to. It also supports the co‐agency of educators and school leaders to apply the charter so that it aligns with the school’s culture and processes. Importantly, the charter provides the guiding principles for working together, but requires relationships, trust, co‐investment, and practical tools of implementation to be meaningfully enacted. Box 5 demonstrates how this has been tested and implemented on Darumbal Country, Rockhampton, Central Queensland.

Limitations

This study prioritised broad engagement with First Nations education stakeholders, particularly young people. It did not, however, focus on the ways in which gender identity or sex may influence the experiences of First Nations learners. In addition, the team did not collect detailed information on participants’ socio‐economic background, language, profession, gender. Although this lens may have added valuable insights, the research team’s capacity did not extend to exploring this dimension in depth. Recruitment, while broad, relied heavily on existing networks of the First Nations team and partners engaged in the social lab. The purpose was to engage stakeholders, especially young people, where a relationship and trust had already been established. However, a broader range of recruitment strategies could have added value to the diversity of stakeholders engaged in the social lab.

Conclusion

Connection allows First Nations people to view the world holistically. This is the foundation of Indigenous learning and wellbeing. A nationwide and self‐determined education has always existed for First Nations learners. It has always centred Indigenous peoples’ rights to be well, to continue cultural practices and to exercise other inherent Indigenous rights. The First Nations team in the Learning Creates Australia Social Lab asserts a learning system determined by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people — a system that ensures Australia’s learning ecosystem is connected to the truth of our past, cares for our people and planet in the present, and prepares future generations to create a healthy, fair, just and equitable society.

Box 1 – Conceptual framework of Indigenous learning journeys

Source: Figure developed for this study by Learning Creates Australia.

Box 2 – Key learning ambitions and values, and key challenges, across the different Indigenous learning journeys

|

Learning ambitions and values |

Challenges |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Box 3 – Story of Aboriginal boarding school experience

|

Journey: learner going back and forth, and learner living off Country; Aboriginal young person, 18 years old |

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Story shared by Aboriginal young person who attended boarding school in Adelaide, and grew up in a regional South Australian town, but holds cultural connections to Mparntwe and the Flinders Ranges. The young person shared how they made the decision to pursue boarding school to better prepare themselves for their future tertiary studies away from home. |

|||||||||||||||

|

“I felt like I needed to move away and get an education so that I could bring it back and help my mob. I wanted to learn more things that I wouldn’t get from [the local high school].” |

|||||||||||||||

|

During the student’s boarding school experience, they shared experiences of not feeling like they could share their Indigenous language, and that they would only speak language with other Aboriginal students at the boarding school. The student had a strong desire to continue learning their language, despite attending boarding school, even if there was no additional support provided by the school to pursue this. |

|||||||||||||||

|

“When I was going to [boarding school], I knew I had to keep learning language, even if it was just calling mum and asking questions, or spending time with my aunty and she taught me a lot of stories. It was important to have language and culture.” |

|||||||||||||||

|

“The school didn’t realise that while I was learning at school, I was also learning my language and culture and there was a lot of balancing.” |

|||||||||||||||

|

“I’d rather know more about my culture and language than having a good ATAR; even though ATAR is important, you can always go back to your land.” |

|||||||||||||||

|

The student also shared the sacrifice involved in going to boarding school. To continue with their studies, the student shared that family support and encouragement was critical. |

|||||||||||||||

|

“Me and my family is strong in language and culture, we go back to Country every 2 months, so going to the city I had to be prepared that I wouldn’t see my land as much. It ended up being that I only went back once a year.” |

|||||||||||||||

|

“We’d use school holidays up to go back to Country. By year 11, I started to feel use to it, then one night I had to leave school for a week, so that I could go back to Country. This was the hardest year, and I was close to dropping out.” |

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

ATAR = Australian Tertiary Admission Rank. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 4 – Visual representation of the Indigenous Nation‐led learning charter*

* Underpinned by Indigenous sovereignty as defined by the First Nations Information Governance Centre reference.19

Box 5 – Tununba Learning Charter, Darumbal Nunthi

|

Testing the Indigenous Nation‐led learning charter model on Darumbal Nunthi (Country) |

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

The First Nations team co‐conveners drew upon their own cultural connections and responsibilities as Darumbal people, to critically engage with and test the charter model on Darumbal Nunthi (Country). This process was actively guided by Darumbal Elders and supported by key local stakeholders, notably the education team of the Darumbal People Aboriginal Corporation. The co‐convenors explicitly framed this relational approach as essential to ensuring this initiative was accountable to Darumbal Elders, Country and community. |

|||||||||||||||

|

Darumbal Elders articulated the 100‐year aspirations for learning on Darumbal Country. At the core of their multigenerational educational aspirations was the statement “for our rivers to keep flowing”. This is remarkably different to what formal education values, as it links learning to cultural, environmental, and generational wellbeing. |

|||||||||||||||

|

North Rockhampton State High School, under the endorsement of school leadership, emerged as a foundation site that we could collaborate with, and at which we could explore embedding the charter within schools. |

|||||||||||||||

|

Workshops facilitated with the school’s educators and students identified key tools for implementation and, through the process, built trust and relationships between the charter team, school staff and students. This initial engagement was a crucial starting place for developing and nurturing a community of practice across local high schools, collectively engaging with Learning Creates Australia, the National Indigenous Youth Education Coalition, Darumbal Elders and broader community representatives. Over 4 years, this evolved organically into a multisectoral community of practice encompassing six schools, including public, Catholic, Indigenous‐independent, and independent institutions. |

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Received 1 May 2025, accepted 19 September 2025

- Hayley McQuire1,2

- Melinda Mann3

- 1 National Indigenous Youth Education Coalition, Melbourne, VIC

- 2 Learning Creates Australia, Melbourne, VIC

- 3 Central Queensland University, Rockhampton, QLD

Data Sharing:

The de‐identified data we analysed are not publicly available, but requests to the corresponding author for the data will be considered on a case‐by‐case basis.

This article is included in a supplement which was funded by the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation (VicHealth). VicHealth is a pioneer in health promotion. It was established by the Victorian Parliament as part of the Tobacco Act 1987 and has a primary focus on promoting good health for all and preventing chronic disease. The funding sources had no role in the planning, writing or publication of the work.

Hayley McQuire is the Chief Executive Officer and co‐founder of the National Indigenous Youth Education Coalition and Co‐Chair of Learning Creates Australia.

Author contributions:

Hayley McQuire: Conceptualization, data curation, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, validation, visualization, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Melinda Mann: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, visualization, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing.

- 1. Hand S, Marsden B, Keynes M, Thomas A. The School Exclusion Project research report. Melbourne: National Indigenous Youth Education Coalition, 2024. https://www.niyec.com/knowledge‐base/the‐school‐exclusion‐project‐span‐classsqsrte‐text‐color‐blackresearch‐reportspan (viewed Sept 2025).

- 2. Australian Government Productivity Commission. Closing the Gap Information Repository — socio‐economic outcome area 5: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students achieve their full learning potential. https://www.pc.gov.au/closing‐the‐gap‐data/dashboard/se/outcome‐area5 (viewed Apr 2025).

- 3. Verbunt E, Luke J, Paradies Y, et al. Cultural determinants of health for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people – a narrative overview of reviews. Int J Equity Health 2021; 20: 181.

- 4. Australian Human Rights Commission. UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. https://humanrights.gov.au/our‐work/un‐declaration‐rights‐indigenous‐people (viewed Apr 2025).

- 5. National Indigenous Youth Education Coalition. NIYEC strategic plan 2020–2025. https://www.niyec.com/our‐story (viewed Sept 2025).

- 6. Rigney LI. Aboriginal child as knowledge producer: bringing into dialogue Indigenist epistemologies and culturally responsive pedagogies for schooling. In: Hokowhitu B, Moreton‐Robinson A, Tuhiwai‐Smith L, et al, editors. Routledge handbook of critical Indigenous studies. Abingdon: Routledge, 2021; pp. 578‐590

- 7. Australian Government Productivity Commission. Closing the Gap Information Repository — socio‐economic outcome area 7: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth are engaged in employment or education. https://www.pc.gov.au/closing‐the‐gap‐data/dashboard/se/outcome‐area7 (viewed Apr 2025).

- 8. Learning Creates Australia. Systems approach. https://www.learningcreates.org.au/approach (viewed Apr 2025).

- 9. McQuire H. A self‐determined First Nations leadership model. Dec 2021. https://www.learningcreates.org.au/2021/12/01/self‐determined‐first‐nations‐leadership‐model (viewed Apr 2025).

- 10. Lycett K, Cleary J, Calder R, et al. A framework for the Future Healthy Countdown 2030: tracking the health and wellbeing of children and young people to hold Australia to account. Med J Aust 2023; 219: S3‐S10. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2023/219/10/framework‐future‐healthy‐countdown‐2030‐tracking‐health‐and‐wellbeing‐children

- 11. O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, et al. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine 2014; 89: 1245–1251.

- 12. Lewis D, et al. From community‐based participatory research (CBPR) involving Indigenous peoples to Indigenous‐led CBPR: it is more than just drinking tea. J High Educ Outreach Engagem 2025; 29: 199‐218.

- 13. Rigney D, Bignall B, Vivian A, Hemming S. Indigenous Nation building and the political determinants of health and wellbeing: discussion paper. Melbourne: Lowitja Institute, 2022. https://www.lowitja.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/2023/05/LI_IndNatBuild_DiscPaper_0822.pdf (viewed Apr 2025).

- 14. Thornton S, Graham M, Burgh G. Place‐based philosophical education: reconstructing ‘place’, reconstructing ethics. Childhood Philos 2021; 17: 1‐29.

- 15. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission. Recognition, rights and reform: a report to government on native title social justice measures 1995. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service, 1995. https://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi‐bin/viewdoc/au/journals/AILR/1996/27.html (viewed Apr 2025).

- 16. Ridgeway A. Mabo ten years on—small step or giant leap? In: Treaty: let’s get it right! Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press, 2003; pp. 185‐197.

- 17. Brigg M. Engaging Indigenous knowledges: from sovereign to relational knowers. Aust J Indig Educ 2016; 45: 152‐158.

- 18. Moreton‐Robinson A. Incommensurable sovereignties: Indigenous ontology matters. In: Hokowhitu B, Moreton‐Robinson A, Tuhiwai‐Smith L, et al, editors. Routledge handbook of critical indigenous studies. Abingdon: Routledge, 2021; pp. 257‐268.

- 19. First Nations Information Governance Centre. First Nations data sovereignty in Canada. Stat J IAOS 2019; 35: 47‐69.

- 20. International Conference on Health Promoting Universities and Colleges. Okanagan Charter: an international charter for health promoting universities and colleges. Kelowna: ICHPUC, 2015. https://president.media.uconn.edu/wp‐content/uploads/sites/3778/2024/04/Okanagan_Charter_Oct_6_2015.pdf (viewed Apr 2025).

Abstract

Objective: To explore how redesigning learner recognition systems can value First Nations students’ diverse knowledges and skills, facilitating systemic educational reform aligned with Indigenous definitions of success, wellbeing, and sense of belonging.

Design: Social lab methods employing iterative co‐design, guided by First Nations‐led frameworks aligned with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, ensuring community accountability and Indigenous self‐determination.

Setting: This study was part of the Learner’s Journey Social Lab facilitated by Learning Creates Australia, which was conducted from 1 October 2020 to 31 October 2021. The First Nations team was co‐convened in partnership with the National Indigenous Youth Education Coalition.

Participants: Seventy‐two participants from First Nations communities, including students and young people (aged 14–25 years), educators, community representatives, allied health professionals, policy makers, and academics.

Process: Development of an Indigenous Nation‐led learning charter model, informed by thematic analysis of interviews and a focus group exploring First Nations students’ learning journeys, ambitions, and social and cultural determinants of wellbeing.

Values: Recognition and validation of Indigenous learning journeys; alignment of educational practices with cultural determinants of social and emotional wellbeing through the development of an Indigenous Nation‐led learning charter; and enhanced agency, belonging and First Nations‐defined success in educational environments.

Results: The Indigenous Nation‐led learning charter was developed to support student sense of belonging; facilitate wellbeing‐centred relationships and partnerships between schools, communities, and custodians; and increase student engagement and agency through recognition of cultural, community, and identity‐related learning. The charter model is supported and implemented through a place‐based community of practice and learner wellbeing recognition tool.

Conclusion: Centring Indigenous sovereignty, self‐determination and wellbeing necessitates significant shifts in educational practice and relationships, ultimately supporting holistic learner success and community wellbeing.