The known: Australian emergency psychiatry units are a mainstay of inpatient treatment for people at risk of suicide. However, nothing is known about the experience of the clinicians working in these wards.

The new: Emergency psychiatry units are subject to conflicting demands related to resource allocation and expectations regarding the management of suicide risk. This tension causes anxiety that can be alleviated by a flat team hierarchy and clear treatment protocols.

The implications: Defined care models and effective, evidence‐based inpatient treatment frameworks for people at risk of suicide are essential for the wellbeing of people working in emergency psychiatry units.

Given the international shortage of mental health clinicians1,2 and rising levels of compassion fatigue among acute mental health services staff,3 reflected locally by the mass resignation of hospital psychiatrists in New South Wales,4 understanding the experiences of mental health clinicians in acute care is important. In Australia, psychiatric emergency care centres (PECCs) assess and provide short term treatment for people in crisis, particularly those at risk of suicide. Designed for people with “low to medium acuity mental health problems” and “who are likely to require only brief (up to 48 hours) period of time in hospital”,5 PECCs were introduced to improve collaboration between psychiatric and emergency services and to be collocated with emergency departments (EDs). The services themselves, however, were not standardised, and triage processes and service provision within EDs vary according to local requirements.5 Bed numbers, governance, and length of stay also vary between centres.

A PECC requires a stable team of experienced staff, but we know little about the factors that influence staff wellbeing.6 The experiences of psychiatric nurses have been extensively investigated,7,8,9 including with respect to patient coercion10 and restraint (felt to be unpleasant but necessary11), compassion fatigue9 (mitigated by strong leadership, positive workplace culture, clinical supervision, reflection, self‐care, and personal wellbeing), and the relationship of anger with the perceived acceptability of but not the degree of coercion8 and aggression (mental health nurses experience more abuse than other nurses).12 Less is known about other acute mental health care professionals. Psychiatric trainees for whom psychiatry was not the first choice of specialty are more likely to report burnout,13 but enforcing work hour limits, supervision, and stress management tools reduce the risk;14 positive work experiences require high quality supervision, supported autonomy, and witnessing patient recovery.15

Managing people at risk of suicide can evoke uncomfortable emotions,16 intense countertransference reactions such as anxiety, confusion, and anger (in psychiatry residents)17 and rejection and inadequacy (in psychiatric nurses).18 As individuals experiencing suicidality comprise most of the people seen in emergency psychiatric units such as PECCs, it is possible that the experiences of PECC staff may be different to that of clinicians in other care settings. Research into clinician experiences in this regard has been limited to specialised borderline personality disorder units in the United States and the Netherlands;19,20,21 none has been undertaken in Australian emergency psychiatric inpatient units. Information about the clinician experience is required for developing operational frameworks for these complex, often distressing environments.

We therefore examined the experiences of people in various disciplines working in New South Wales PECCs to identify factors that influence their wellbeing and how they are managed.

Methods

The study reported in this article is part of a broader qualitative study that is evaluating care models and staff practices in New South Wales PECCs.22 We report our study according to the Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research checklist (COREQ).23

Setting and participants

The study was undertaken in eleven of the twelve New South Wales PECCs: Blacktown Hospital, Calvary Mater Hospital (Newcastle), Campbelltown Hospital, Liverpool Hospital, Nepean Hospital (Penrith), Prince of Wales Hospital, Royal North Shore Hospital, Shellharbour Hospital, St George Hospital, St Vincent’s Hospital Sydney, and Wollongong Hospital (Box 1); the non‐participating unit did not respond to our enquiries. We also interviewed two NSW Health administrators. The clinical director of each unit, as the designated principal investigator, identified potential participants in the unit; purposive sampling (maximum four people per unit) was used to obtain multidisciplinary representation across the eleven units. Nurses, social workers, psychiatrists, psychiatry registrars, hospital managers, and NSW Health staff were eligible to participate if they were working in or had management oversight of PECCs. Further details about the participants and their relationships with the investigators are included in the Supporting Information, part 1.

Data collection

During 22 June 2023 – 20 February 2024, semi‐structured interviews using questions developed by authors JH, NG, and AM (Supporting Information, part 2) were undertaken, with one or two participants at a time. We aimed not for data saturation but to comprehensively examine staff practices in all PECCs by purposively sampling all participating units. After each participant provided informed consent in an online form and received information about the study from author JH (or AM, at JH’s clinical workplace, St Vincent’s Hospital), semi‐structured interviews (mean duration, 50 minutes) were conducted by a PECC psychiatrist (JH) or psychologist (AM, at JH’s workplace). Participants were not financially compensated. The interviews were transcribed using the transcription feature of Microsoft Teams, and the data were cleaned and anonymised by JH.

Analysis

We analysed the interview transcripts thematically using a semantic and latent focus24 and an experiential relativist framework. Data were analysed iteratively by a psychiatrist (author JH), peer worker (KF), Aboriginal health worker (JC), clinical nurse consultant (MB), and senior manager/nurse (SE). First, JH familiarised herself with all transcripts; KF, JC, MB, and SE each familiarised themselves with up to four transcripts. Each reader then generated initial codes, followed by a series of meetings, in which codes and then initial themes were created using memos, a cork board, and paper. JH coded all transcripts and each other analyst coded one to three transcripts in NVivo 14, aiming for deeper understanding and assessing code appropriateness. All analysts participated in a codebook and further theme development. The themes were refined in a reflexive process and iteratively discussed with authors AM and NG as they were identified. All transcripts were coded and checked, and ten were each coded by two analysts. A report of the results was prepared by the team and a lay summary for the participants. Information about the investigators, including their reflexivity statement, is included in the Supporting Information, part 1.

Ethics approval

The St Vincent’s Human Research and Ethics Committee approved the study (2022/PID00456).

Results

We interviewed 35 people from eleven units and at NSW Health (two to four per unit; nineteen men, sixteen women): eleven senior nurses (including eight administrators: five with and three without clinical responsibilities), nine psychiatrists (including five administrators: four with and one without clinical responsibilities), seven psychiatry registrars, three junior nurses, two social workers, one occupational therapist (an administrator without clinical responsibilities), one hospital administrator without clinical training, and two NSW Health staff administrators (one with, one without clinical training; neither with clinical responsibilities). The interviewees included nine hospital managers with clinical responsibility (four clinical directors, five nurse unit managers) and five without clinical responsibility. Psychiatry work experience duration ranged from two weeks to 35 years, and interviewees had up to ten years’ non‐continuous experience in PECCs.

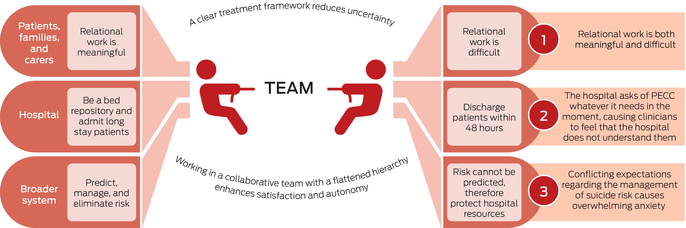

The overarching finding was that working in PECCs involved conflicting and concurrent demands (Box 2). We identified three areas of dissonance: working with people at risk of suicide and their families and carers led to intense, exhausting, and sometimes intolerable emotions, but also connection and a sense of reward; conflicting system expectations that suicide risk must be contained by admitting people to hospital and that, as the risk cannot be contained, people should be discharged from hospital; and PECCs should both provide long stay admissions and function as short stay units.

Clinicians reported that these tensions often led to unmanageable anxiety that could leave them feeling uncertain and not having control without two protective factors: clearly defined treatment frameworks that either acknowledged or helped manage these tensions; and support from the collaborative, flat hierarchical team structure in their units, which enhanced control and autonomy.

Interactions with the patient: relational work is both meaningful and difficult

Participants simultaneously experienced satisfaction and intensely uncomfortable emotions. The more pleasant emotional experiences involved human connectedness and feedback about a job well done. However, these feelings were coupled with strong emotions, as frequently and passionately raised by participants. This was a gruelling daily experience that senior staff members believed harmed junior staff, exacerbated by feeling overwhelmed by the number of people clinicians are expected to manage. Interestingly, specific emotions were not labelled; instead, clinicians described the amount or effect of the emotion, such as “exhausting” and “intense” (participants 8 and 9) or “transference is just very, very strong” (participant 1), possibly because they do not feel free to discuss specific unpleasant emotions related to patients. Staff described doing their best to manage, but this was reported neither confidently nor often (Box 3).

Interactions with the health care system: conflicting expectations regarding the management of suicide risk causes overwhelming anxiety

PECCs were seen as the major focus of suicide risk in inpatient facilities. “Risk” was frequently mentioned, including in the context of risk tolerance, risk containment, and risk ownership. Clinicians acknowledged that “it’s impossible to predict risk” (participant 20) but felt under pressure to measure, manage, and take responsibility for it. Senior nurses described feeling responsible for “taking the risk” of harm for discharged patients (participants 2 and 3), despite being unable to control it. The burden of risk ownership and the anxiety it caused were frequent themes, reflecting the conflict between the reality of unpredictable risk and the expectation of eliminating it (Box 4).

The knowledge that suicide risk is unpredictable was associated with justification of protecting limited system resources. Participants noted the expectation for clinicians to make “risky” decisions without a clear framework for doing so, and not making these decisions being viewed as an abnegation of responsibility. A senior nurse described how external system pressure on their lead clinician to take risks led to team‐wide “apprehension”. Some participants (clinicians and administrators) reported that clinicians with conservative approaches to risk are seen less favourably than those who can tolerate the anxiety of discharging a patient at risk of harm (Box 4).

Clinicians perceived the dual expectation to ensure safe care while making risky decisions to conserve resources. It was suggested that the anxiety caused by these conflicting expectations contributed to poor retention of psychiatrists. Clinical directors noted that the psychiatrists bear a heavy burden with respect to suicides because of anxiety‐provoking scrutiny, particularly from the coroner (Box 4).

Interactions with the hospital: the hospital asks for whatever it needs in the moment, causing clinicians to feel that it does not understand the PECC care model

PECCs managed patients with complex biopsychosocial problems, the “Swiss army knife of psychiatry” (participant 6), which the system does not see or understand, as recognition of this complexity has faded (Box 5).

This perceived lack of understanding was related by participants to two diametrically opposing stances. On the one hand, clinicians were under pressure to discharge people within the 48 hour period specified by the NSW Health model of care,5 despite the complexity of patient needs and limited unit resources. On the other, most clinicians felt compelled to fill beds with people expected to require longer admissions when ED capacity had been exceeded and the long stay inpatient ward was full; PECCs are used to manage bed numbers rather than as part of a care model. This feeling was noted by interviewees at all seniority levels. Clinicians felt their ability to ease system pressure was undervalued, noting that rapid turnover reduces lengths of stay by providing non‐specialist care, and lower bed occupancy facilitates flexibility and more rapid flow of patients through the ED (Box 5).

Clinicians also felt they did not have the resources to manage the complexity of the patients in their care. Social workers, in particular, felt under pressure to change the social circumstances of individuals despite their limited options, feeling set up to fail by system‐level features beyond their control. Helplessness was felt by staff who could not effect change for people living in distressing circumstances, particularly units without dedicated social workers or drug and alcohol services. This led to perceptions that the system was unjust and fragmented, with few outpatient resources, angering clinicians who felt under pressure to make decisions without the appropriate resources (Box 5).

Protective factors and processes

A clear treatment framework reduces uncertainty

The perceived clarity of the local treatment framework affected the experience of clinicians within the team and their interactions with patients. A clear treatment framework provides a sense of stability and satisfaction for clinicians and of continuity of care for service users. Clinicians who spoke about their treatment frameworks with precision and confidence were more likely to describe enjoyment in their role, a better running system and team, and better patient experience. Conversely, those who reported that the treatment approach was not clear often felt unsure of themselves and their clinical efficacy, felt that their scope of practice was poorly defined, and were frustrated in their ability to effect change. This feeling was expressed at all seniority levels (Box 6).

Working in a collaborative team with a flat hierarchy enhances satisfaction and autonomy

Comments about job satisfaction or enjoyment were often related to team function. Most teams were described by their staff as highly collaborative, compassionate and holistic, and interviewees valued their working relationships. Social workers and senior nurses frequently and favourably referred to the flat hierarchy of PECCs, as well as commenting that working in PECCs was more challenging (in a positive sense) than acute inpatient wards. Other positive interprofessional experiences reported by senior nurses and registrars concerned specific senior team members and highlighted the importance of an experienced and calming presence in the ward (Box 7).

Discussion

We report the first study to qualitatively investigate the experiences of clinicians working in emergency psychiatric units (PECCs), undertaken by an investigator team with varied skills and perspectives. Our study is also timely, given the unrest among psychiatrists in the New South Wales public health system. Overall, we found that clinicians view PECCs as characterised by co‐occurring, opposing pressures that reflect both resource limitations and conflicting cultural views of risk.

Inadequate connections between care system groups cause problems with understanding other people in the system

We found a clear divide between “us” (the team) and “them” (the hospital and health system). This divide is unsurprising, given the pressure of the PECC environment, where conflicting priorities and intense emotions are common. Stressful environments often lead to close knit, polarised groups, with both positive and negative consequences.25 They enable staff to manage emotional demands, but people in polarised groups often have trouble understanding people from outside their own group. The adaptive mentalisation‐based integrative treatment (AMBIT) framework emphasises the importance of connections with the broader system without which “a tightly interconnected … team is condemned to … [relying] on a pretence of self‐sufficiency.”25 These connectors must be epistemically trustworthy; that is, they must be trusted to provide relevant, generalisable information. Establishing connectors in PECCs is complicated by complex system interfaces, but epistemic trust between clinicians and management is imperative for managing the tensions between care model fidelity, expectations about managing risk, and limited hospital resources. Constant mentalising (understanding one’s own and others’ mental states through thoughts, feelings, and intentions) between teams is hard work, and requires a relational framework for this purpose.

To relieve the tension associated with managing suicide risk, let us instead concentrate on minimising suffering

Clinicians report that they are expected to predict and manage risk by admitting people as inpatients, but also to discharge people to conserve resources or to limit admissions to accommodate transfers from the ED. This tension is reflected in the literature. Risk prediction and stratification for clinical decision‐making are regarded as futile in psychiatry,26 and the evidence that hospitalising people with suicidal ideation prevents suicides is limited.7 Nevertheless, in emergency psychiatry the term “risk assessment” is often used synonymously with “clinical assessment”, and the term “zero suicides” has been discussed in the academic literature as fostering blame and inappropriate guilt in clinicians if future harm is not predicted.27 The dissonance between clinicians’ knowledge of the evidence for what they do, and the social discussion of suicide, supports their perception of conflicting expectations that provoke anxiety. Given the limited ability to prevent suicide, it might be better to give priority to goals other than identifying suicide risk factors, instead concentrating on elements associated with distress and self‐harm28 to alleviate suffering. Clinicians could then avoid the conflicting expectations of managing risk through admission and discharge. Mental health professionals could reduce the tension by incorporating empirical evidence into staff training, educating patients, families, and carers, and ensuring that this evidence is reflected in policy and care models.

Clinician wellbeing will require action

Clinician wellbeing was a recurrent motif in the interviews. The job demands–resources theory (JDRT), a framework for assessing how psychosocial work factors affect wellbeing,29 suggests that conflicting or high work demands without adequate supporting resources leads to distress and burnout, whereas autonomy, control, and collegial and managerial support reduce the risk.

Clinicians in PECCs report experiences that can be directly related to this framework: constant conflicting demands regarding resource use (accepting people for potentially long stays but remaining a short stay unit), conflicting expectations regarding risk management (protecting people at risk of suicide by admitting them but acknowledging that admission does not reduce the suicide risk), and the emotional challenges of the work itself.

It may not be possible to reduce some of these demands in emergency psychiatry. However, we found that the impact of these conflicting demands could be mitigated by a clear treatment framework. This finding illustrates the JDRT buffering effect of enhancing autonomy and control to reduce the job strain caused by high demands and low control. The organisational details need further consideration, but AMBIT and mentalisation frameworks could be applicable, offering both an emergency psychiatry treatment framework30 and enhancing autonomy and support.25 This approach merits future examination for improving clinician wellbeing, retention, and patient care. The participants also reported collegiality arising from collaborative, flat hierarchy teams, but this finding could reflect recruitment bias in our study. Reducing staff turnover and increasing managerial and team support31 could improve the staff experience.

The recent mass resignation of psychiatrists from the New South Wales public health system,4 after this study was completed, indicates that system improvement is important for clinician wellbeing. In drawing attention to an ailing system, the resignations have probably exacerbated the sense of conflicting expectations among remaining clinicians. The pressure on PECCs to perform outside their intended model of care may increase, and the staff experience deteriorate further. While a clear treatment framework and clarity about expectations regarding risk management are imperative, adequate funding and staffing and must come first, “organised around a mentalised understanding of the needs and wishes of the client rather than the requirements of the specific agency in which a worker is employed.”32

Future directions for research and policy

Organisational interventions to enhance clinician and manager wellbeing, rather than relying on individual approaches, are available but are infrequently implemented and rarely evaluated. A recent review found that fewer than 10% of interventions for enhancing clinician wellbeing were organisationally focused.33 Frameworks to design and evaluate such interventions are available31 and have been embedded in legal regulations.34 We identified key targets for developing and testing organisational approaches, including aligning suicide risk assessment and prevention with published evidence, reconsidering treatment goals, and reducing conflicting organisational demands.

The important and sometimes fraught relationships between emergency psychiatry and ED clinicians should be investigated further, as well as the experience of service users and their families and carers. In particular, we need evidence about situations in which there are disagreements — within families and care networks, or between families and care networks, service users, and clinicians — regarding treatment decisions, including the use of detention under the Mental Health Act.

Limitations

We aimed for full representation of PECC clinicians in New South Wales, but emergency psychiatry units in other Australian states may have different perspectives to those we have reported. The sample size was kept small to facilitate intensive qualitative analysis, but the generalisability of our findings is unknown. We do not know how many people declined to participate in the study. All authors are health researchers, narrowing the analytical focus.

Conclusion

People working in PECCs experience tension and, at times, considerable anxiety arising not just from the intense emotional demands of crisis care but also from the conflicting demands and expectations of the system in which they work. This tension reduces staff wellbeing and retention, and consequently patient care. These negative effects can be reduced by team cohesion and having a clear treatment framework. Our findings could help identify and evaluate organisational approaches to improving the wellbeing of people in these demanding roles.

Box 1 – Work arrangements for the eleven New South Wales psychiatric emergency care centres (PECCs) that participated in our study

|

Centre |

Emergency department (ED) coverage by psychiatric emergency care centre team |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

1 |

8.30 am–5 pm: the PECC and ED are both covered entirely by the PECC team (consultant, registrar, two clinical nurse consultants, social worker, junior medical officers). The PECC team also provides an assessment and treatment service to a psychiatric, drug, alcohol, and non‐prescription drug overdose ward attached to the PECC and ED. 5–10 pm: on‐site hospital registrar, clinical nurse consultant for the ED. Psychiatrically trained registered nurses governed by PECC are based in the ED. |

||||||||||||||

|

2 |

8.30 am–5 pm: PECC consultant covers the ED; registrar does not. Psychiatric services for the ED are provided by clinical nurse consultants, who do not cover the PECC. After 5 pm: clinical nurse consultants in the ED, on‐call hospital registrar. |

||||||||||||||

|

3 |

8.30 am–5 pm: PECC consultant and registrar cover both the ED and PECC. One psychiatric clinical nurse consultant covers the ED only until 10 pm; after 10 pm: on‐site hospital registrar. |

||||||||||||||

|

4 |

8.30 am–5 pm: PECC consultant covers the ED; ED is also covered by two clinical nurse consultants and an unaccredited registrar from another hospital. According to demand, the PECC registrar can be called on to cover the ED. After 5 pm: on‐site hospital registrar. |

||||||||||||||

|

5 |

8.30 am–5 pm: PECC consultant available solely for phone calls from clinicians covering the ED; PECC registrar covers ED in person. After 5 pm: on‐site hospital registrar. |

||||||||||||||

|

6 |

8.30 am–5 pm: the ED is covered by two clinical nurse consultants, and two non‐PECC registrars who also cover the crisis team; career medical officer covers the PECC; all can be sent to the PECC if required. After 5 pm: clinical nurse consultants for the ED (until 10 pm) and on‐site hospital registrar. |

||||||||||||||

|

7 |

Mental health‐specific ED; general ED staffed by psychiatric registrars and nurses; PECC team does not cover the ED. After 5 pm: on‐site hospital registrar. |

||||||||||||||

|

8 |

8.30 am–5 pm: both the ED and PECC are covered by the PECC consultant and registrar; ED also has an ED‐only psychiatric clinical nurse consultant. After 5 pm: on‐site hospital registrar. |

||||||||||||||

|

9 |

PECC is a mental health ED, with access to four short stay emergency mental health inpatient beds. Patients are triaged in the attached general ED and transferred to the PECC, where they are tended by the PECC team in the same way as an ED tends people with non‐psychiatric problems. The PECC team can also perform assessments in the general ED. PECC is available 24 hours a day. |

||||||||||||||

|

10 |

8.30 am–5 pm: The ED is covered by several mental health clinical nurse consultants and the PECC consultant, and the PECC registrar for one hour each morning and then a dedicated ED psychiatry registrar. After 5–10 pm: Clinical nurse consultants and on‐site hospital registrar covers ED. |

||||||||||||||

|

11 |

This unit moved from the ED to a separate area about two years ago. Instead of the PECC, services in the ED are provided by clinical nurse consultants and clinical nurse specialists and a daily roster of registrars; psychiatrists provide an on‐call phone service at all times. |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Box 2 – The conflicting organisational and care system demands associated with working in New South Wales psychiatric emergency care centres: summary of findings from 35 interviews, 22 June 2023 – 20 February 2024

Box 3 – Interactions with the patient: relational work is both meaningful and difficult. Illustrative quotes

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

PECC = psychiatric emergency care centre. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 4 – Interactions with the health care system: conflicting expectations regarding the management of suicide risk causes overwhelming anxiety. Illustrative quotes

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

PECC = psychiatric emergency care centre; ED = emergency department. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 5 – Interactions with the hospital: the hospital asks for whatever it needs in the moment, causing clinicians to feel that it does not understand the PECC care model. Illustrative quotes

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

PECC = psychiatric emergency care centre; ED = emergency department. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 6 – A clear treatment framework reduces uncertainty. Illustrative quotes

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

PECC = psychiatric emergency care centre. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 7 – Working in a collaborative team with a flat hierarchy enhances satisfaction and autonomy. Illustrative quotes

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

PECC = psychiatric emergency care centre. |

|||||||||||||||

Received 16 October 2024, accepted 10 March 2025

- Jacqueline P Huber1,2

- Alyssa Milton3

- Matthew Brewer1

- Kat Fry1

- Sean Evans1

- Jason Coulthard1

- Nicholas Glozier3

- 1 St Vincent’s Hospital Sydney, Sydney, NSW

- 2 The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW

- 3 ARC Centre of Excellence for Children and Families over the Life Course, Sydney, NSW

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Sydney, as part of the Wiley – The University of Sydney agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

[Correction added on 22 August 2025, after first online publication: CAUL funding statement has been added.]

Data Sharing:

The data for this study will not be shared, as we do not have permission from the participants or ethics approval to do so.

We thank the following people who acted as principal investigators: Nicholas Babidge (South East Sydney Local Health District), Tad Tietze (Illawarra Shoalhaven Local Health District), Raphael Fraser (Western Sydney Local Health District), Alison Sutton (Royal North Shore Hospital), Katherine McGill (Hunter New England Local Health District, University of Newcastle), Kristof Mikes‐Liu (Nepean Blue Mountains Local Health District), and Tuni Bhattacharayya (South West Sydney Local Health District). The ARC Centre of Excellence for Children and Families over the Life Course provided general help with research writing and supported networking opportunities and general learning. Jacqueline Huber holds a Trisno Family PhD Scholarship from the RANZCP Foundation.

No relevant disclosures.

Author contributions:

Jacqueline P. Huber: conceptualisation, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, writing (original draft, review and editing), funding acquisition. Alyssa Milton: conceptualisation, data curation, investigation, methodology, project administration, supervision, writing (review and editing). Matthew Brewer: conceptualisation, formal analysis, writing (review and editing). Kat Fry: conceptualisation, formal analysis, writing (review and editing). Jason Coulthard: conceptualisation, formal analysis, writing (review and editing). Sean Evans: conceptualisation, formal analysis, writing (review and editing). Nicholas Glozier: conceptualisation, data curation, investigation, methodology, project administration, supervision, writing (review and editing).

- 1. Butryn T, Bryant L, Marchionni C, Sholevar F. The shortage of psychiatrists and other mental health providers: causes, current state, and potential solutions. Int J Acad Med 2017; 3: 5–9.

- 2. Every‐Palmer S, Grant ML, Thabrew H, et al. Not heading in the right direction: five hundred psychiatrists’ views on resourcing, demand, and workforce across New Zealand mental health services. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2024; 58: 82–91.

- 3. Liberati E, Richards N, Ratnayake S, et al. Tackling the erosion of compassion in acute mental health services. BMJ 2023; 382: e073055.

- 4. Block S. Psychiatrists in NSW threaten to resign over a pay dispute. InSight+, 3 Feb 2025. https://insightplus.mja.com.au/2025/4/psychiatrists‐in‐nsw‐threaten‐to‐resign‐over‐a‐pay‐dispute (viewed July 2025).

- 5. NSW Health. Psychiatric emergencey care centre model of care guideline (GL2015_009). 3 Sept 2015. https://www1.health.nsw.gov.au/pds/ActivePDSDocuments/GL2015_009.pdf (viewed June 2025).

- 6. Huber JP, Milton A, Brewer MC, et al. The effectiveness of brief non‐pharmacological interventions in emergency departments and psychiatric inpatient units for people in crisis: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2024; 58: 207–226.

- 7. Jalil R, Dickens GL. Systematic review of studies of mental health nurses’ experience of anger and of its relationships with their attitudes and practice. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2018; 25: 201–213.

- 8. Marshman C, Hansen A, Munro I. Compassion fatigue in mental health nurses: a systematic review. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2022; 29: 529–543.

- 9. McCluskey A, Watson C, Nugent L, et al. Psychiatric nurse’s perceptions of their interactions with people who hear voices: a qualitative systematic review and thematic analysis. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2022; 29: 395–407.

- 10. Doedens P, Vermeulen J, Boyette LL, et al. Influence of nursing staff attitudes and characteristics on the use of coercive measures in acute mental health services: a systematic review. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2020; 27: 446–459.

- 11. Wong WK, Bressington DT. Nurses’ attitudes towards the use of physical restraint in psychiatric care: a systematic review of qualitative and quantitative studies. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2022; 29: 659–675.

- 12. Edward KL, Stephenson J, Ousey K, et al. A systematic review and meta‐analysis of factors that relate to aggression perpetrated against nurses by patients/relatives or staff. J Clin Nurs 2016; 25: 289–299.

- 13. Jovanović N, Podlesek A, Volpe U, et al. Burnout syndrome among psychiatric trainees in 22 countries: risk increased by long working hours, lack of supervision, and psychiatry not being first career choice. Eur Psychiatry 2016; 32: 34–41.

- 14. Chan MK, Chew QH, Sim K. Burnout and associated factors in psychiatry residents: a systematic review. Int J Med Educ 2019; 10: 149–160.

- 15. Karageorge A, Llewellyn A, Nash L, et al. Psychiatry training experiences: a narrative synthesis. Australas Psychiatry 2016; 24: 308–312.

- 16. Michaud L, Greenway KT, Corbeil S, et al. Countertransference towards suicidal patients: a systematic review. Curr Psychol 2021; 42: 416–430.

- 17. Dressler DM, Prusoff B, Mark H, et al. Clinician attitudes toward the suicide attempter. J Nerv Ment Dis 1975; 160: 146–155.

- 18. Rossberg JI, Friis S. Staff members’ emotional reactions to aggressive and suicidal behavior of inpatients. Psychiatr Serv 2003; 54: 1388–1394.

- 19. Lindkvist R‐M, Landgren K, Liljedahl SI, et al. Predictable, collaborative and safe: healthcare provider experiences of introducing brief admissions by self‐referral for self‐harming and suicidal persons with a history of extensive psychiatric inpatient care. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2019; 40: 548–556.

- 20. Eckerstrom J, Allenius E, Helleman M, et al. Brief admission (BA) for patients with emotional instability and self‐harm: nurses’ perspectives: person‐centred care in clinical practice. Int J Qual Stud Health Well‐being 2019; 14: 1667133.

- 21. Nehls N. Brief hospital treatment plans for persons with borderline personality disorder: perspectives of inpatient psychiatric nurses and community mental health center clinicians. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 1994; 8: 303–311.

- 22. Huber J, Milton A, Brewer M, et al. What is the purpose of psychiatric emergency care centres? A qualitative study of health care staff. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2025; 59: 552–563.

- 23. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32‐item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007; 19: 349–357.

- 24. Clarke V, Braun V. 10 fundamentals of qualitative research. In: Successful qualitative research: a practical guide for beginners. London: SAGE Publications, 2013; pp 19–41.

- 25. Bevington D, Dangerfield M. Meeting you where you are: one mentalizing stance, and the many versions needed in (non‐)mentalizing systems of help. J Infant Child Adolesc Psychother 2024; 23: 85–95.

- 26. Wang M, Swaraj S, Chung D, et al. Meta‐analysis of suicide rates among people discharged from non‐psychiatric settings after presentation with suicidal thoughts or behaviours. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2019; 139: 472–483.

- 27. Mokkenstorm JK, Kerkhof AJFM, Smit JH, Beekman ATF. Is it rational to pursue zero suicides among patients in health care? Suicide Life Threat Behav 2018; 48: 745–754.

- 28. Large MM, Ryan CJ, Carter G, Kapur N. Can we usefully stratify patients according to suicide risk? BMJ 2017; 359: j4627.

- 29. Bakker AB, Demerouti E. Job demands‐resources theory: taking stock and looking forward. J Occup Health Psychol 2017; 22: 273–285.

- 30. Bateman A, Fonagy P, Campbell C, et al. Mentalizing and emergency care. In: Cambridge guide to mentalization‐based treatment (MBT). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023; pp 364–387.

- 31. Deady M, Sanatkar S, Tan L, et al. A mentally healthy framework to guide employers and policy makers. Front Public Health 2024; 12: 1430540.

- 32. Bevington D, Fuggle P, Cracknell L, et al. Adopting the AMBIT approach to changing wider systems of help. In: Adaptive mentalization‐based integrative treatment: a guide for teams to develop systems of care. New York: Oxford University Press, 2017; pp 351–373 (here: p 357).

- 33. Cohen C, Pignata S, Bezak E, et al. Workplace interventions to improve well‐being and reduce burnout for nurses, physicians and allied healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2023; 13: e071203.

- 34. NSW Government. Work health and safety regulation 2017. Current: 1 Mar 2025. https://legislation.nsw.gov.au/view/html/inforce/current/sl‐2017‐0404 (viewed July 2025).

Abstract

Objectives: To examine the experiences of people in various disciplines working in New South Wales psychiatric emergency care centres (PECCs) to identify factors that influence their wellbeing and how they are managed.

Study design: Qualitative study; semi‐structured interviews.

Setting: Eleven of twelve New South Wales PECCs, NSW Health.

Participants: Thirty‐five nurses, psychiatrists, psychiatry registrars, social workers, occupational therapists, and NSW Health staff working in or with management oversight of PECCs.

Main outcome measures: Experiential relativist framework analysis of the experiences of people working in PECCs.

Results: The overarching finding was that working in PECCs involved conflicting, concurrent demands. Three major themes were identified: interactions with the patient: relational work is both meaningful and difficult; interactions with the health care system: conflicting expectations regarding the management of suicide risk causes overwhelming anxiety; and interactions with the hospital: the hospital asks for whatever it needs in the moment, causing clinicians to feel that it does not understand the PECC care model. Two protective factors and processes were also identified: a clear treatment framework reduces uncertainty, enhancing clinician satisfaction and continuity of care for patients; and working in a collaborative team with a flat hierarchy enhances satisfaction and autonomy.

Conclusion: People working in PECCs experience tension and, at times, considerable anxiety arising not just from the intense emotional demands of crisis care but also from the conflicting demands and expectations of the system in which they work. This tension reduces staff wellbeing and retention, and consequently patient care. These negative effects can be reduced by team cohesion and having a clear treatment framework.