Unprofessional abortion referral practices are a threat to person‐centred abortion care. Evidence globally shows that unprofessional abortion referral practices can generate misinformation, communicate judgement, and hinder timely access to care — causing distress and harm to abortion seekers.1,2,3,4,5,6 These harmful referral practices occur across the health care workforce and are not limited to individuals claiming a conscientious objection.1,2,3,4,5,6 This suggests a need to define best practice for abortion referral and encourage professionalism in referral practices. Addressing this gap, this perspective article: (i) applies the principles of medical professionalism to abortion referral, (ii) proposes a minimum standard for professional abortion referral, and (iii) identifies strategies across the health system to promote person‐centred referrals.

Does guidance exist to promote professional referral practices?

Policy discussions around refusal to participate in abortion care (eg, conscientious objection) often focus on whether the health practitioner is willing to refer an abortion seeker to a willing provider.5 Refusing practitioners who do refer are assumed to be acting in line with professional standards, while those who do not refer are generally seen as unprofessional and obstructing care. Although this focus on willingness to refer is warranted, particularly as referral is legally obligated in many jurisdictions,5 we argue that the act of providing an abortion referral is necessary but not sufficient to meet professional standards. How a referral is carried out is also a critical component of the professional obligations towards abortion seekers.

Abortion‐specific guidelines are clear that practitioners who refuse to participate in abortion should refer their patients onwards. For example, the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists Clinical guideline for abortion care states that practitioners who have a conscientious objection to abortion should “inform the woman how to access the closest provider of abortion services within a clinically reasonable time” and “must not impose delay, distress or health consequences on a woman seeking an abortion”, but does not provide further details.7

Medical codes of conduct provide additional guidance for ethical and professional behaviour, but these are often broadly worded and cover the entire scope of practice. The Medical Board of Australia Good medical practice: a code of conduct for doctors in Australia states that all providers should act in their “patients’ best interests when making referrals” and that their personal views should not “adversely affect the care of your patient or the referrals you make”.8

There is also specific guidance for conscientious objection. The Australian Medical Association's position statement on conscientious objection tells practitioners to treat patients with “dignity and respect”, “minimise disruption to patient care”, and not “impede patients’ access to care”.9 The code of conduct similarly states that a doctor's conscientious objection should not “impede access to treatments that are legal”.8

Despite the relevance of this guidance, there is ample evidence of a disconnect between real‐world abortion referral practices1,2,3,4,5,6 and the principles outlined in professional codes of conduct and clinical guidelines (Box 1).7,8,9 Strategies are urgently needed to ensure that practitioners refer patients for abortion in a professional manner.

A spectrum of abortion referral practices

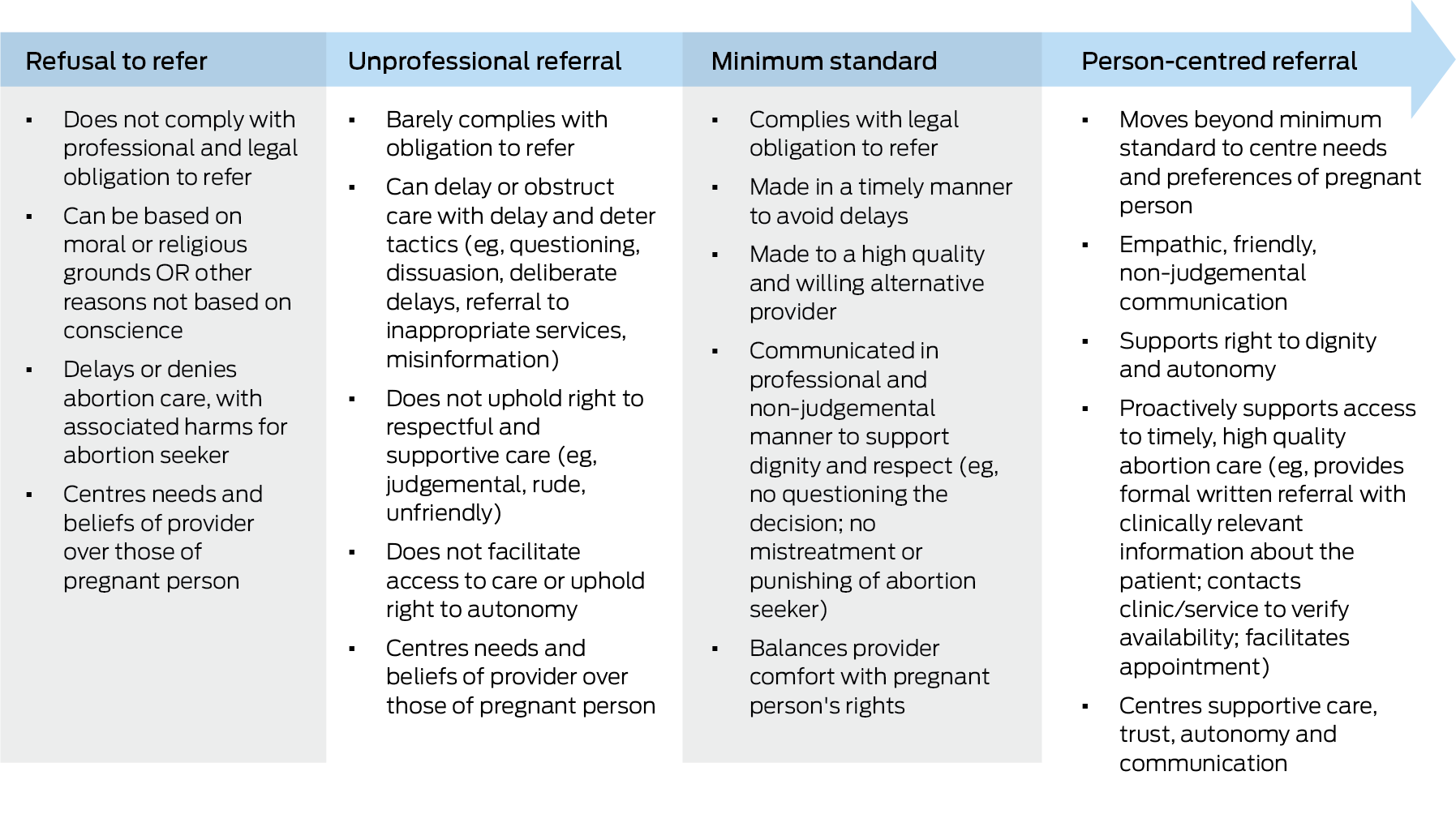

Applying principles of medical professionalism to abortion referrals, we present a spectrum of practices, from refusal to refer to person‐centred referral, and propose a minimum standard for professional abortion referral (Box 2).

Refusal to refer

Among health practitioners who refuse to refer their patients for abortion care, some have moral or religious grounds (conscientious objection), whereas others have reasons that are not conscience‐based, such as discomfort, stigma, or fear of repercussions.1,5 Regardless of reason or objection status, refusing to refer violates a range of professional codes of conduct (Box 1). There are also legal considerations; in many jurisdictions, referral is legally obligated if practitioners refuse to provide abortion care for conscience reasons.10 Yet in practice, referral by objectors is inconsistently carried out and rarely enforced.1

Refusal to refer is a well documented barrier to abortion.1,11 It harms patients by delaying care, which can increase costs and travel, constrain choice of abortion methods, and potentially lead to denial of care, with economic, educational, and emotional consequences.1,4,5,12

Unprofessional referral

Even among providers who do refer for abortion, referral practices can advertently or inadvertently obstruct access.3,5 Unprofessional referrals include rude, unfriendly, or judgemental communication, seeking to delay abortion access (eg, ordering unnecessary tests), or knowingly referring to a service that will not provide an abortion (eg, adoption clinic, pregnancy crisis centre, or objecting provider) — these practices have been documented across Australia3,4,5,6 and elsewhere.1 Such unprofessional referrals violate codes of conduct and medical guidance focused on respect and facilitating care, yet are rarely the focus of efforts to improve abortion access.

In practice, unprofessional referrals from health practitioners who refuse to participate in abortion can delay care, cause under‐ or misinformation, cause emotional distress to abortion seekers, and increase their reluctance to seek further abortion care.2,3 These impacts are similar to those of refusal to refer.

Minimum professional standards for abortion referral

In accordance with medical guidance and professional codes of conduct (Box 1), professional referral practices should encompass both how a referral is communicated and the information that is delivered. We propose that, at a minimum, an abortion referral must be (i) timely, (ii) communicated in a non‐judgemental manner (eg, without questioning the decision or punishing the patient for seeking abortion care), and (iii) be made to a high quality and willing provider who can provide abortion care or refer the patient onwards (eg, a general practitioner without a conscientious objection). Importantly, professional referral practices must comply with jurisdictional legal requirements. These requirements vary, with some allowing information provision only and others requiring referral. For example, in Victoria, an objecting provider is required to refer to someone else in the same profession who does not have an objection.5

To support professional referral practices, referral pathways for abortion care must be systematised so that all health practitioners have clear and accessible information about where to refer for high quality care,13 for example through state‐based hotlines such as 1800MyOptions in Victoria.

Person‐centred referral

A person‐centred referral moves beyond minimum professional standards to centre the needs and preferences of the abortion seeker (rather than the health practitioner). Person‐centred referrals are part of “care that is respectful of and responsive to people's preferences, needs and values, and which empowers people to take charge of their own SRH [sexual and reproductive health]”.14 They support the pregnant person's right to dignity and autonomy by facilitating access to timely, high quality abortion care in a friendly and empathic way. For example, a referring health practitioner could send a formal written referral with clinically relevant information about the patient to a willing practitioner or service, or can contact the clinician or service (including pathology or sonography, as required) to verify their availability. They centre supportive care, trust, autonomy and communication, which are key domains of person‐centred abortion care.2

What can be done to move health practitioners along the continuum towards person‐centred referral practices?

The importance of person‐centred referral can be reinforced at various levels across the health system.

Professional bodies have a critical role in articulating and enforcing professional standards and codes of conduct — with a focus on regulating medical professionalism rather than over‐regulating abortion. Medical guidelines should clearly articulate standards for professional abortion referral practices. Medical education should train future providers on person‐centred referral, including through values clarification approaches. Colleges and training pathways can provide practical training. This is particularly relevant in general practice, the discipline responsible for most referrals in Australia.13 Government regulators, such as the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (Ahpra), have a responsibility to develop effective reporting and enforcement mechanisms for individuals who avoid their professional obligations for abortion referral. All of these actors should also ensure that clear referral pathways for abortion exist and are shared with health practitioners, to facilitate professional referral practices.13

Health service policies and management can ensure that all staff are aware of their professional and legal obligations to refer respectfully for abortion. They can support practitioners to recognise person‐centred referral as part of high quality care. Across the health system, person‐centred referral could become a measure of quality or performance. Quality improvement interventions can promote respectful referral practices grounded in empathy, a core principle of person‐centred care.14 Strategies to promote empathy can draw on evidence that abortion seekers fear being judged, are unsure about their options, and are worried about whether they will be able to access the time‐sensitive service.2,3,4,6 This type of information can be integrated into stigma‐reduction approaches such as values clarification workshops, which support health practitioners to consider their professional responsibilities towards abortion seekers.15

At the individual health practitioner level, anyone providing referrals can reflect on whether they are — intentionally or unintentionally — referring in a way that does not fit with person‐centred care principles. There may be a role for bystander interventions in which health practitioners who hear about unprofessional referrals can share resources about the harms of unprofessional referral and support colleagues to understand the minimum standards for abortion referral.

Conclusion

Unprofessional referral practices undermine equitable access to person‐centred abortion care. In this perspective article, we have argued the importance of encouraging all health practitioners, regardless of objector status, to move along the spectrum towards person‐centred referral. Importantly, the specifics of how to achieve this will vary depending on medical guidelines, legal context, and institutional environment. This is a call for professional bodies, regulators, medical colleges, medical education, and the health system to integrate guidance on professional abortion referral practices and ensure these standards are monitored and enforced.

Box 1 – Codes of conduct, professional guidance, and legal frameworks relevant to abortion referral practices in Australia

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Referral‐specific principles: |

|

||||||||||||||

|

General good practice principles: |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Conscientious objection to any health service: |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Conscientious objection to any health service: |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Conscientious objection to abortion specifically: |

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Ahpra = Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency; AMA = Australian Medical Association; RANZCOG = Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. |

|||||||||||||||

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- 1. de Londras F, Cleeve A, Rodriguez MI, et al. The impact of ‘conscientious objection’ on abortion‐related outcomes: a synthesis of legal and health evidence. Health Policy 2023; 129: 104716.

- 2. Self B, Maxwell C, Fleming V. The missing voices in the conscientious objection debate: British service users’ experiences of conscientious objection to abortion. BMC Med Ethics 2023; 24: 65.

- 3. Makleff S, Belfrage M, Wickramasinghe S, et al. Typologies of interactions between abortion seekers and healthcare workers in Australia: a qualitative study exploring the impact of stigma on quality of care. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2023; 23: 646.

- 4. Vallury KD, Kelleher D, Mohd Soffi AS, et al. Systemic delays to abortion access undermine the health and rights of abortion seekers across Australia. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2023; 63: 612‐615.

- 5. Keogh LA, Gillam L, Bismark M, et al. Conscientious objection to abortion, the law and its implementation in Victoria, Australia: perspectives of abortion service providers. BMC Med Ethics 2019; 20: 11.

- 6. Noonan A, Black KI, Luscombe GM, Tomnay J. “Almost like it was really underground”: a qualitative study of women's experiences locating services for unintended pregnancy in a rural Australian health system. Sex Reprod Health Matters 2023; 31: 2213899.

- 7. The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Clinical guideline for abortion care: an evidence‐based guideline on abortion care in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand. Melbourne, Australia: RANZCOG; 2023. https://ranzcog.edu.au/wp‐content/uploads/Clinical‐Guideline‐Abortion‐Care.pdf (viewed Jan 2025).

- 8. Medical Board Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency. Good medical practice: a code of conduct for doctors in Australia. Melbourne, Australia: Medical Board Ahpra; 2020. https://www.medicalboard.gov.au/Codes‐Guidelines‐Policies/Code‐of‐conduct.aspx (viewed Apr 2025).

- 9. Australian Medical Association. AMA position statement: conscientious objection ‐ 2019[website]. AMA; 2019. https://www.ama.com.au/position‐statement/conscientious‐objection‐2019 (viewed Jan 2025).

- 10. Lavelanet AF, Johnson BR, Ganatra B. Global Abortion Policies Database: a descriptive analysis of the regulatory and policy environment related to abortion. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2020; 62: 25‐35.

- 11. Sorhaindo AM, Lavelanet AF. Why does abortion stigma matter? A scoping review and hybrid analysis of qualitative evidence illustrating the role of stigma in the quality of abortion care. Soc Sci Med 2022; 311: 115271.

- 12. Foster DG. The turnaway study: ten years, a thousand women, and the consequences of having‐‐or being denied‐‐an abortion. New York: Scribner Book Company; 2020.

- 13. Srinivasan S, Botfield JR, Mazza D. Utilising HealthPathways to understand the availability of public abortion in Australia. Aust J Prim Health 2022; 29: 260‐267.

- 14. Afulani PA, Nakphong MK, Sudhinaraset M. Person‐centred sexual and reproductive health: a call for standardized measurement. Health Expect 2023; 26: 1384‐1390.

- 15. Turner KL, Pearson E, George A, Andersen KL. Values clarification workshops to improve abortion knowledge, attitudes and intentions: a pre‐post assessment in 12 countries. Reprod Health 2018; 15: 40.

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Melbourne, as part of the Wiley ‐ The University of Melbourne agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

We acknowledge the contributions of participants of prior studies, who generously shared information with us that has informed the ideas shared in this commentary. We also acknowledge our collaborators on various other projects that have also inspired the thinking in this piece.

Kirsten Black is chair of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists Sexual and Reproductive Health Special Interest Group.

Author contribution statement:

Makleff S: Conceptualization, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Merner B: Conceptualization, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Black KI: Interpretation, writing – review and editing. Keogh L: Interpretation, writing – review and editing.