Primary care services in Australia and overseas are challenged by population growth, ageing populations, inadequate financial support, and workforce shortages; these challenges in turn place pressure on other, more expensive components of health care, including emergency departments and hospitals.1 Many governments are responding by seeking greater equity, efficiency, and effectiveness in health care delivery by reforming both preventive and responsive primary care.2 In Australia, this is being achieved by implementing the recommendations of the Strengthening Medicare Taskforce.3

Enrolment — linking or registering a person with a specific general practitioner or family physician or with a single general practice — is one component of high performing primary care that benefits patients, general practitioners, general practices, and the community by supporting greater continuity and coordination of care,4,5 leading to better health outcomes.6 Enrolment provides relational, informational, and management continuity7 at a single point of care or medical home.4,5,8,9,10 In turn, continuity of care is expected to lead to improved health, reduce inappropriate health service use and costs, and improve patient satisfaction.5,6,7,10,11,12,13

Patient enrolment also benefits practices by informing resource allocation,8 supporting screening for and managing chronic conditions,4,8 and increasing productivity.14 Patient enrolment can provide additional information to government agencies that supports health system planning, preventive care, and the development of primary care reforms, including context‐specific funding reforms.4,8,15,16,17

Prior to 2023, Australia was among the few Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development countries to not have a system of patient enrolment.1 In 2023, 76.9% of Australians reported they had a usual general practitioner,18 but the freedom to seek care from multiple practices is likely to reduce continuity of care, particularly given the lack of informational continuity across practices.19 Voluntary patient registration (MyMedicare; Supporting Information, part 1) was introduced in Australia in October 2023 to support continuity of care and provide a platform for primary care funding reform.20 MyMedicare is supported by additional Medicare incentives for enrolled patients.21

We undertook a scoping review of publications about the enablers of and barriers to voluntary patient enrolment in general practices, and its impact on quality of care, in order to assess the likely effectiveness of MyMedicare with respect to improving continuity of care and supporting other primary care reforms in Australia.

Methods

A scoping review seeks to establish what is known about the evidence for an intervention or about a research question or concept. We report our review according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA‐ScR) statement.22

Study design

We included in our review peer‐reviewed journal articles published in English during 1 January 2014 – 12 July 2024 that reviewed or evaluated primary care patient enrolment. We selected this period to focus attention on recent primary care that may be relevant to reforms in Australia. We included original research articles that reported the form of enrolment and the enablers of or barriers to enrolment; we did not include studies of informal registration, payment models, or registration outside primary care unless they were directly related to patient enrolment (Supporting Information, table 1).

We used a standardised search protocol to identify relevant studies in PubMed, the Cochrane Register of Systematic Reviews, Embase, CINAHL (Cumulated Index in Nursing and Allied Health Literature), PsycINFO, PAIS (Public Affairs Information Service), Web of Science, and Scopus: {‘primary care’ OR ‘general practice’ OR ‘primary health care’ OR ‘primary healthcare’} AND {‘patient registration’ OR ‘patient enrolment’ OR ‘patient empanelment’ OR ‘patient rostering’} in {Title Abstract Keyword}. Searches were conducted by author SB on 12 July 2024.

All search results were entered into an Excel (Microsoft) spreadsheet and duplicate records were removed. The first two authors reviewed the titles and abstracts and removed articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria; articles were included for full text review if the two authors disagreed about their relevance. The bibliographies of included articles were checked for further relevant publications.

Data extraction and management

The data extraction template included the author, title, publication details, and abstract; for articles considered potentially relevant based on their title and abstract, we recorded the jurisdiction, study objective, method, findings, whether enrolment was voluntary or compulsory, form of enrolment, and any associated reforms and enablers of enrolment. Authors SB and JL reviewed the full text and documented the reasons for excluding articles. This detailed record keeping allowed the analysis to be checked by the co‐authors.

Data synthesis

The results were analysed thematically and grouped by research question and emerging themes.

Results

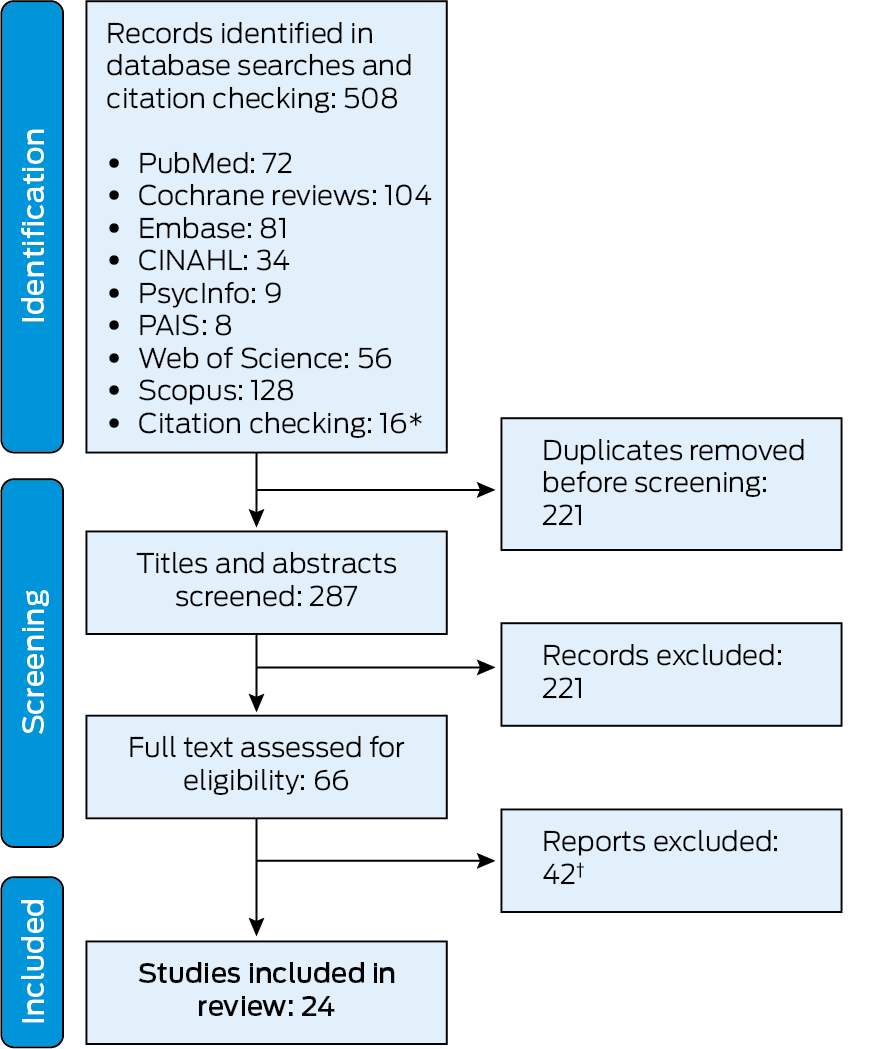

The database searches and bibliography checks identified 508 potentially relevant articles. After removing duplicates and screening their titles and abstracts, we reviewed the full text of 66 articles; 24 met the inclusion criteria for our scoping review (Box 1, Box 2).23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46 Twenty‐two of the included studies were undertaken in fifteen countries: eleven in Canada, four in Australia, two each in the United Kingdom and New Zealand, and one each in Ireland, the United States, and France. One publication compared schemes in twelve countries (Denmark, France, Germany, Ireland, Israel, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Canada [Ontario], Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom), and one was a rapid review. The four Australian articles38,40,45,46 described trial interventions; they were included because of the similarities of the interventions with MyMedicare. Several schemes operate concurrently in Canada42 and Ireland,23 facilitating a degree of practitioner and consumer choice, and model comparison.

Characteristics of patient enrolment schemes

Patient enrolment was not introduced as a standalone intervention in any country. It was introduced as part of macro‐level reforms that provided universal health care coverage before the 1980s (Denmark, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Sweden, United Kingdom); meso‐level primary care reforms (Canada, Germany, Israel, Norway, Switzerland); and micro‐level reforms for cost containment (France).37 Enrolment was combined with initiatives for grouping physicians into larger practices,28,31 to introduce multidisciplinary team‐based primary care,30,41,42,45 and to specifically target people at high risk of poor health outcomes, including people with chronic health conditions or complex mental illness, and older people likely to have multiple health conditions.30,38,40,45,46 Enrolment was introduced in health systems with various models of primary care financing, including capitation, blended, and fee‐for‐service models.31,32,37,38,40,42,45,46

Most enrolment schemes were voluntary, but the options varied markedly with regard to whether practices or patients were registered, where patients registered, which services were available to enrolled patients, and limitations or penalties for attending another practice. The only mandatory allocated scheme at the time registration was introduced was that in Italy.37

Advantages and disadvantages of enrolment

The reported advantages of enrolment were related to clinical service delivery. Enrolment allowed better planning, the use of multidisciplinary teams, and greater efficiency and more income for practices.25,30,45

The multi‐jurisdictional study found that the effectiveness of patient registration for improving continuity of care and other health outcomes had been little investigated, particularly its effectiveness independent of other reforms.37 Country‐specific studies also found little or no effect of registration on continuity of care. In two countries where patients were already registered with practices, an additional requirement to register with an “accountable general practitioner” for people over 75 years of age (United Kingdom) or a “preferred doctor” (France) was introduced, suggesting that continuity of care might be better achieved at the general practitioner level;24,29 neither study identified subsequent improvements in continuity of care.

The effect of enrolment accompanied by other reforms on emergency department use was mixed. Two studies in Ontario and one in Quebec found that the number of emergency department presentations and hospital admissions did not change;25,31,34 a second Quebec study found that emergency department use was reduced by 3%.26 The differences in the findings could be related to the enrolment process, associated reforms, or the study methodology.

In some studies, enrolment was found to be a barrier to primary care access and continuity of care, as indicated by waiting lists for registration;27,35,41,43 some groups, often of marginalised people, not being registered;32,33,36,44 and less continuity of care for people registered with a practice rather than a physician.34 Comparisons of jurisdictions with different models of enrolment and primary care found that some models suited some groups more than others;14,26,28 for example, enrolment of immigrants in Ontario was three times as high with capitation models as for family health teams.33 Enrolment of people with significant mental illness in Ontario was also lower than for the general population when the practice incentives to enrol people with complex needs were capped.42 (Box 3).

Enablers and barriers to enrolment

People are more likely to enrol with a general practitioner or practice when they perceive that it benefits them, regardless of the service funding model.33,39 Their preference for continuity of care was indicated by the fact that their choice of “usual general practitioner” was not necessarily based on convenience or proximity.23,38 Older people (for example, people aged 45 years or older39), women, people from higher socio‐economic areas, and people with chronic or multiple medical conditions were both more likely to enrol in voluntary registration schemes and to have usual general practitioners than younger people (for example, people aged 15–24 years36), men, and people from marginalised groups, including recent migrants and First Nations people.27,33,36,39,44

The multifaceted nature of primary care models made it unclear which enablers of and barriers to enrolment had the greatest impact. Practices were likely to register patients if encouraged by the payment model, regardless of the specific payment model.8,25 Practices were discouraged from registering people if the model was complex or the capacity of the practice had been reached.35,41 Further, funding models needed to adequately support practices to register people with complex health needs to ensure that the patients receive appropriate care42 and that practices do not register only people with fewer care needs27 (Box 4).

In summary, the characteristics of patient enrolment models in different countries differ greatly in both form and implementation. No specific model improved continuity of care while providing a mechanism for delivering other reforms.

Discussion

The implications of the findings of our scoping review are relevant to the two objectives of the Australian patient enrolment reforms (MyMedicare) introduced in October 2023: to improve continuity of care, and to provide a platform for funding reform.21,47

Contrary to expectations, we found little evidence that patient registration improves continuity of care. This finding may reflect strong affiliations with usual general practitioners prior to enrolment for people who would benefit most from continuity of care, including older people and those with chronic health conditions; further, both enrolment and research were focused on such people.38,42,45,46 Improved continuity of care could be more noticeable among people who do not have usual general practitioners, but they were not investigated in the studies reviewed.

Enrolment was sometimes associated with reduced continuity of care, because of difficulty obtaining an appointment with a preferred general practitioner,25 care shifting from a usual general practitioner to another person in the practice,34 practices possibly focusing on people with less complex needs,27,35,42 or difficulty in enrolling with a practice,27,35,41 particularly for people from specific groups, such as recent migrants.35 As enrolment was often part of broader reform, change may be driven or limited by factors associated with other changes. If funding was inadequate or the reforms were complex, enrolment was associated with poorer outcomes for patients, general practitioners, and practices.48

We found that the nature of enrolment and associated reforms and rates of enrolment each varied according to the administrative mechanism, associated incentives, and the cultural and operational context. This included the degree of choice as to whether or where to enrol, the level of choice at the practice, and the incentives or disincentives associated with enrolment. For example, enrolment in some countries was associated with better access to services or financial incentives (lower out‐of‐pocket costs). Rates of enrolment were lower in schemes with weaker incentives. Enrolment mechanisms and rates should be further investigated to determine whether the same factors drive enrolment overall and for particular patient groups; those who are not currently experiencing continuity of care should be identified, as should those who could particularly benefit from enrolment. Enrolment is likely to benefit everyone with respect to relational and informational continuity, and may facilitate improved funding of primary care.

High enrolment rates are required to support primary care funding reforms; from the viewpoint of the health care system, the attachment of patients to usual general practitioners is insufficient, as they are not discouraged from visiting several practices.19 MyMedicare offers only limited incentives for practices, general practitioners, or patients that encourage enrolment or patients to use a single provider. Enrolment should be closely monitored to determine why practices and patients participate in enrolment, to ensure that the scheme facilitates continuity of care and further reforms. In addition to monitoring overall enrolment, the enrolment of specific groups who may experience barriers to health care access should be specifically monitored,49 including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, residents of rural and remote Australia, older Australians, people with mental illness or disability, people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, and LGBTIQ+ people.20

For MyMedicare to work, practices and patients need to see value in enrolment. This will be difficult to establish without more targeted evaluation of its benefits, not just for those who have usual general practitioners, but also for those who do not. The limited incentives offered by MyMedicare mean that it is an opportunity for studying the impact of patient registration on continuity of care when most people may not benefit from the incentives.

When reforms have multiple purposes, as with MyMedicare, their implementation requires consideration of how each aim will be achieved. Incentives are needed to encourage continuity of care for both practices and patients, supporting relational, informational, and management continuity of care. Incentives are also needed to encourage enrolment to enable the delivery of other reforms, including financial support for this behavioural change and its administration. The design of incentives should take potential unintended consequences into account and ensure equitable access.

Limitations

First, our review of articles published during 2014–24 focused on more recent meso‐ and micro‐level primary care reforms.37 While recent reforms are likely to be more relevant to Australia, less recent macro‐level reforms, such as the introduction of the National Health Service in the United Kingdom, could also be relevant. Further, other schemes may not yet have been reported in the literature. Second, characteristics of enrolment schemes were reported differently in the included publications. Most were described as voluntary, but the choices and limitations for practices and patients differed substantially between and within jurisdictions. Third, continuity of care in primary care leads to better patient outcomes,7,11,13 and it is assumed that patient enrolment enables continuity of care and consequently better patient outcomes.4 However, as patients often prefer to see their usual general practitioners, enrolment may simply formalise an existing preference. The studies we included often involved patients likely to benefit most from continuity of care and therefore likely to already have preferred practitioners, such as people over 65 years of age or with chronic illnesses, so they did not have many additional benefits from enrolment. Fourth, people's preferences and behaviours can be deeply embedded and take time to change; patient behaviour and how patient enrolment can be most effective encouraged requires further investigation.

Conclusions

Patient enrolment often has the dual purpose of improving continuity of care and supporting primary care service delivery and reforms. We found some evidence of enrolment improving efficiency in primary care delivery, but little that it improves continuity, quality, or the equity of primary care. This may reflect the fact that many people have preferred practitioners and thereby naturally select continuity of care. When different funding and enrolment models operate concurrently, unintended outcomes are possible, including people in marginalised groups or with complex care needs being less likely to enrol and use primary care. Further investigation of the diversity of patient enrolment schemes and their impact on both continuity of care and supporting primary care reform is needed, and the engagement of practitioners and patients with MyMedicare should be closely monitored, both overall and for specific groups of people.

Received 5 August 2024, accepted 12 November 2024

Box 1 – Identification and selection of articles for inclusion in the scoping review of published studies of the enrolment of patients in primary care, 2014–24

CINAHL = Cumulated Index in Nursing and Allied Health Literature; PAIS = Public Affairs Information Service.* Of the sixteen publications identified by citation checking, two were excluded after screening their titles and abstracts, and ten were excluded after full text review.† Detailed reasons for exclusion are provided in the Supporting Information, part 2.

Box 2 – Summary of articles included in the scoping review of published studies of patient enrolment in primary care, 2014–24

|

Reference, location |

Study summary |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Carmody and Whitford (2007),23 |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Dourgnon et al. (2007),24* |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Glazier et al. (2009),25 |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Tiagi et al. (2014),26 |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Breton et al. (2015),27 |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Kiran et al. (2015),28 |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Barker et al. (2016),29* |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Christiansen et al. (2016),30 |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Strumpf et al. (2017),31 |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Burch et al. (2018),32 |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Batista et al. (2019),33 |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Singh et al. (2019)34 |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Breton et al. (2021),35 |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Irurzun‐Lopez et al. (2021),36 |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Marchildon et al. (2021),37 |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Bonney et al. (2022),38 |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Lavergne et al. (2022),39 |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Reed et al. (2022),40* |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Smithman et al. (2022),41 |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Bayoumi et al. (2023),42 |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Nabieva et al. (2023)43* |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Pledger et al. (2023),44 |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Javanparast et al. (2024),45 |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Reed et al. (2024),46 |

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

* Publications identified by checking bibliographies of eligible publications identified by database searching. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 3 – Advantages and disadvantages of patient enrolment in primary care reported by publications included in our scoping review

|

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Box 4 – Enablers of and barriers to patient enrolment in primary care reported by publications included in our scoping review

|

Enablers |

Barriers |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

- Shona M Bates1,2

- Jialing Lin1

- Luke Allen3

- Michael Wright1

- Michael Kidd1,3

- 1 International Centre for Future Health Systems, UNSW Sydney, Sydney, NSW

- 2 UNSW Sydney, Sydney, NSW

- 3 University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by University of New South Wales, as part of the Wiley – University of New South Wales agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

The International Centre for Future Health Systems is generously supported by funding from the Ian Potter Foundation.

Luke Allen is a salaried general practitioner and received consultancy payments from the World Health Organization and World Bank for advisory work on primary care reform programs. Michael Wright chairs the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners funding and health system reform expert committee and is chief medical officer at Avant Mutual. Michael Kidd is former deputy chief medical officer with the Australian Department of Health and Aged Care, where he was involved in primary care reform developments.

- 1. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. Realising the potential of primary health care [OECD Health Policy Studies]. 30 May 2020. https://www.oecd‐ilibrary.org/social‐issues‐migration‐health/realising‐the‐potential‐of‐primary‐health‐care_a92adee4‐en (viewed Nov 2024).

- 2. Azimzadeh S, Azami‐Aghdash S, Tabrizi JS, Gholipour K. Reforms and innovations in primary health care in different countries: scoping review. Prim Health Care Res Dev 2024; 25: e22.

- 3. Australian Department of Health and Aged Care. Strengthening Medicare taskforce report. Dec 2022. https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023‐02/strengthening‐medicare‐taskforce‐report_0.pdf (viewed Nov 2024).

- 4. Bodenheimer T, Ghorob A, Willard‐Grace R, Grumbach K. The 10 building blocks of high‐performing primary care. Ann Fam Med 2014; 12: 166‐171.

- 5. Wright M, Versteeg R. Introducing general practice enrolment in Australia: the devil is in the detail. Med J Aust 2021; 214: 400. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2021/214/9/introducing‐general‐practice‐enrolment‐australia‐devil‐detail

- 6. Pereira Gray DJ, Sidaway‐Lee K, White E, et al. Continuity of care with doctors: a matter of life and death? A systematic review of continuity of care and mortality. BMJ Open 2018; 8: e021161.

- 7. Guthrie B, Saultz JW, Freeman GK, Haggerty JL. Continuity of care matters. BMJ 2008; 337: a867.

- 8. Grumbach K, Olayiwola JN. Patient empanelment: the importance of understanding who is at home in the medical home. J Am Board Fam Med 2015; 28: 170‐172.

- 9. Harris MF, Rhee J. Achieving continuity of care in general practice: the impact of patient enrolment on health outcomes. Med J Aust 2022; 216: 460‐461. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2022/216/9/achieving‐continuity‐care‐general‐practice‐impact‐patient‐enrolment‐health

- 10. Wright M, Mainous AG. Can continuity of care in primary care be sustained in the modern health system? Aust J Gen Pract 2018; 47: 667‐669.

- 11. Van Walraven C, Oake N, Jennings A, Forster AJ. The association between continuity of care and outcomes: a systematic and critical review. J Eval Clin Pract 2010; 16: 947‐956.

- 12. World Health Organization. Continuity and coordination of care: a practice brief to support implementation of the WHO Framework on integrated people‐centred health services. 7 Nov 2018. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241514033 (viewed July 2024).

- 13. Haggerty JL, Reid RJ, Freeman GK, et al. Continuity of care: a multidisciplinary review. BMJ 2003; 327: 1219‐1221.

- 14. Kantarevic J, Kralj B, Weinkauf D. Enhanced fee‐for‐service model and physician productivity: evidence from family health groups in Ontario. J Health Econ 2011; 30: 99‐111.

- 15. Santos F, Conti S, Wolters A. A novel method for identifying care home residents in England: a validation study. Int J Popul Data Sci 2020; 5: 1666.

- 16. Souty C, Turbelin C, Blanchon T, et al. Improving disease incidence estimates in primary care surveillance systems. Popul Health Metr 2014; 12: 19.

- 17. Vahabi M, Lofters A, Kumar M, Glazier RH. Breast cancer screening disparities among urban immigrants: a population‐based study in Ontario, Canada. BMC Public Health 2015; 15: 679.

- 18. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Patient experiences, 2022–23; here: table 5.3. 21 Nov 2023. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/health‐services/patient‐experiences/2022‐23#data‐downloads (viewed June 2024).

- 19. Wright M, Hall J, van Gool K, Haas M. How common is multiple general practice attendance in Australia? Aust J Gen Pract 2018; 47: 289‐296.

- 20. Australian Department of Health. Future focused primary health care: Australia's primary health care 10 year plan 2022–2032. Mar 2022. https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2022/03/australia‐s‐primary‐health‐care‐10‐year‐plan‐2022‐2032.pdf (viewed Nov 2024).

- 21. Australian Department of Health and Aged Care. Information for MyMedicare patients. Updated 20 Aug 2024. https://www.health.gov.au/our‐work/mymedicare/patients (viewed Nov 2024).

- 22. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA‐ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018; 169: 467‐473.

- 23. Carmody P, Whitford DL. Telephone survey of private patients’ views on continuity of care and registration with general practice in Ireland. BMC Fam Pract 2007; 8: 17.

- 24. Dourgnon P, Guillaume S, Naiditch M, Ordonneau C. Introducing gate keeping in France: first assessment of the preferred doctor scheme reform [Issues in Health Economics, no. 124]. July 2007. https://www.irdes.fr/EspaceAnglais/Publications/IrdesPublications/QES124.pdf (viewed Nov 2024).

- 25. Glazier RH, Klein‐Geltink J, Kopp A, Sibley LM. Capitation and enhanced fee‐for‐service models for primary care reform: a population‐based evaluation. CMAJ 2009; 180: E72–E81.

- 26. Tiagi RA, Tiagi R, Chechulin Y. The effect of rostering with a patient enrolment model on emergency department utilization. Healthc Policy 2014; 9: e105‐e121.

- 27. Breton M, Brousselle A, Boivin A, et al. Who gets a family physician through centralized waiting lists? BMC Fam Pract 2015; 16: 10.

- 28. Kiran T, Kopp A, Moineddin R, Glazier RH. Longitudinal evaluation of physician payment reform and team‐based care for chronic disease management and prevention. CMAJ 2015; 187: E494‐E502.

- 29. Barker I, Lloyd T, Steventon A. Effect of a national requirement to introduce named accountable general practitioners for patients aged 75 or older in England: regression discontinuity analysis of general practice utilisation and continuity of care. BMJ Open 2016; 6: e011422.

- 30. Christiansen E, Hampton MD, Sullivan M. Patient empanelment: a strategy to improve continuity and quality of patient care. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract 2016; 28: 423‐428.

- 31. Strumpf E, Ammi M, Diop M, et al. The impact of team‐based primary care on health care services utilization and costs: Quebec's family medicine groups. J Health Econ 2017; 55: 76‐94.

- 32. Burch P, Doran T, Kontopantelis E. Regional variation and predictors of over‐registration in English primary care in 2014: a spatial analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health 2018; 72: 532‐538.

- 33. Batista R, Pottie KC, Dahrouge S, et al. Impact of health care reform on enrolment of immigrants in primary care in Ontario, Canada. Fam Pract 2019; 36: 445‐451.

- 34. Singh J, Dahrouge S, Green ME. The impact of the adoption of a patient rostering model on primary care access and continuity of care in urban family practices in Ontario, Canada. BMC Fam Pract 2019; 20: 52.

- 35. Breton M, Smithman MA, Kreindler SA, et al. Designing centralized waiting lists for attachment to a primary care provider: considerations from a logic analysis. Eval Program Plann 2021; 89: 101962.

- 36. Irurzun‐Lopez M, Jeffreys M, Cumming J. The enrolment gap: who is not enrolling with primary health organizations in Aotearoa New Zealand and what are the implications? An exploration of 2015–2019 administrative data. Int J Equity Health 2021; 20: 93.

- 37. Marchildon GP, Brammli‐Greenberg S, Dayan M, et al. Achieving higher performing primary care through patient registration: a review of twelve high‐income countries. Health Policy 2021; 125: 1507‐1516.

- 38. Bonney A, Russell G, Radford J, et al. Effectiveness of quality incentive payments in general practice (EQuIP‐GP) cluster randomized trial: impact on patient‐reported experience. Fam Pract 2022; 39: 373‐380.

- 39. Lavergne MR, King C, Peterson S, et al; QC‐BC Patient Enrolment Project Team. Patient characteristics associated with enrolment under voluntary programs implemented within fee‐for‐service systems in British Columbia and Quebec: a cross‐sectional study. CMAJ Open 2022; 10: E64‐E73.

- 40. Reed RL, Roeger L, Kwok YH, et al. A general practice intervention for people at risk of poor health outcomes: the Flinders QUEST cluster randomised controlled trial and economic evaluation. Med J Aust 2022; 216: 469‐475. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2022/216/9/general‐practice‐intervention‐people‐risk‐poor‐health‐outcomes‐flinders‐quest

- 41. Smithman MA, Haggerty J, Gaboury I, Breton M. Improved access to and continuity of primary care after attachment to a family physician: longitudinal cohort study on centralized waiting lists for unattached patients in Quebec, Canada. BMC Primary Care. 2022; 23: 238.

- 42. Bayoumi I, Whitehead M, Li W, et al. Association of physician financial incentives with primary care enrolment of adults with serious mental illnesses in Ontario: a retrospective observational population‐based study. CMAJ Open 2023; 11: E1‐E12.

- 43. Nabieva K, McCutcheon T, Liddy C. Connecting unattached patients to comprehensive primary care: a rapid review. Prim Health Care Res Dev 2023; 24: e19.

- 44. Pledger M, Mohan N, Silwal P, Irurzun‐Lopez M. The enrolment gap and the COVID‐19 pandemic: an exploration of routinely collected primary care enrolment data from 2016 to 2023 in Aotearoa New Zealand. J Prim Health Care 2023; 15: 316‐323.

- 45. Javanparast S, Roeger L, Reed RL. General practice staff and patient experiences of a multicomponent intervention for people at high risk of poor health outcomes: a qualitative study. BMC Primary Care 2024; 25: 18.

- 46. Reed RL, Roeger L, Kaambwa B. Two‐year follow‐up of a clustered randomised controlled trial of a multicomponent general practice intervention for people at risk of poor health outcomes. BMC Health Serv Res 2024; 24: 488.

- 47. Australian Department of Health and Aged Care. Information for MyMedicare general practices and healthcare providers. Updated 30 Sept 2024. https://www.health.gov.au/our‐work/mymedicare/practices‐and‐providers (viewed Nov 2024).

- 48. Pearse J, Mazevska D, McElduff P, et al. Evaluation of the Health Care Homes trial. Volume 1: summary report. 29 July 2022. https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2022/08/evaluation‐of‐the‐health‐care‐homes‐trial‐final‐evaluation‐report‐2022.pdf (viewed Nov 2024).

- 49. Bates S, Kayess R, Katz I. What can we learn from disability policy to advance our understanding of how to operationalise intersectionality in Australian policy frameworks? Australian Journal of Public Administration 2024; https://doi.org/10.1111/1467‐8500.12648 (viewed Nov 2024).

Abstract

Objectives: To identify publications examining the enablers of and barriers to patient enrolment in primary care and its impact on continuity and quality of care; to assess the likely effectiveness of voluntary patient enrolment (MyMedicare) in Australia with regard to improving continuity of care and supporting other health care reforms.

Study design: Scoping review of peer‐reviewed journal article published in English during 1 January 2014 – 12 July 2024 that evaluated primary care enrolment models, including patient enrolment enablers and barriers.

Data sources: PubMed, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Embase, CINAHL (Cumulated Index in Nursing and Allied Health Literature), PsycINFO, PAIS (Public Affairs Information Service), Web of Science, Scopus. The bibliographies of included articles were checked for further relevant publications.

Data synthesis: The database searches and bibliography checks identified 508 potentially relevant articles; we reviewed the full text of 66 articles after title and abstract screening, of which 24 publications met our inclusion criteria. Twenty‐two of the included studies were undertaken in fifteen countries, including eleven in Canada, four in Australia, and two each in the United Kingdom and New Zealand; one publication compared schemes in twelve countries, one was a rapid review. The characteristics of patient enrolment models differ greatly between countries in both form and implementation, including the mandatory and voluntary components. We found little evidence that enrolment improved continuity of care. However, existing patient engagement with usual general practitioners was high among participants in many studies, and some studies involved patients who may already have had high levels of continuity of care. There is evidence that enrolment can support primary care reforms, including preventive care and the management of chronic conditions, and that other reforms, such as incentives and increased access to services can affect the enrolment of patients and practices. People in marginalised groups or with complex care needs are less likely to enrol with practices or practitioners.

Conclusions: The Australian voluntary patient enrolment scheme should be continuously evaluated to assess levels of engagement by patients and general practices, drawing on the experiences of other countries in which similar schemes operate. Further assessment of overseas enrolment systems could identify reasons for the different experiences reported, as well as enablers of and barriers to successful implementation and better health outcomes.